A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

To help with further browsing click on the large ‘Initial’ to return to the Early Gospel Singers Introduction, or click another initial to take you to details of more early gospel singers.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

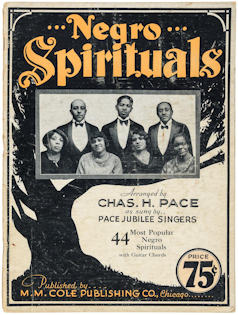

| Name: | Pace Jubilee Singers |

| Location: | Chicago, IL |

| Biography Synopsis: | The group was named for their founder Charles Henry Pace (1886-1963), who by the mid-’20s was mainly active as composer and publisher of religious songs. An ex-student of W.E. Du Bois, Pace moved to Memphis from Atlanta in 1905 to serve as editor of Du Bois’ short-lived periodical the Moon Illustrated Weekly. In 1907, Pace was working as cashier at the Solvent Savings Bank on Beale Avenue when he met W.C. Handy. For years, the two men would collaborate as composers and music publishers, and the Pace & Handy Music Company was founded in 1913, even as Pace sought financial stability by relocating to Atlanta where, like composer Charles Ives, he worked in the life insurance business. In 1921, Pace & Handy dissolved their partnership, and Pace established the Pace Phonograph Company, soon to be known as Black Swan Records. He also became adept as a publisher of Christian melodies, including his own airs and arrangements of traditional spirituals. With Pace as his publisher, hokum bluesman Georgia Tom broke with his longtime collaborator Tampa Red and crossed over to become an exclusively religious artist under the name of Thomas A. Dorsey. According to Memphis musicologist David Evans, Dorsey and Charles Albert Tindley were able to become established in their own careers thanks largely to the groundwork laid by Charles Henry Pace. Several of Tindley’s tunes show up in the Pace Jubilee discography, including “Leave It There,” “Stand by Me,” and “Nothing Between.” The Pace Jubilee Singers made their recordings — more than 40 sides — during the years 1926-1929. Most of these have been reissued by the Document label. They are most significant for the voice of featured soloist Hattie Parker, whose widely imitated sonorities and sensitive handling of spiritual lyrics would later become manifest in the work of the great Mahalia Jackson.

Source: AllMusic.com |

| Recording career: | 1925 – 1929 |

| References / links: | Discography of American Historical Recordings |

| Images: |

|

| Name: | Blind Benny Paris and Wife |

| Location: | |

| Born: | |

| Died: | |

| Biography Synopsis: | |

| Recording career: | |

| Most popular song(s): | |

| Musical Influences: | |

| References / links: | Discography of American Historical Recordings |

| Images: |

| Name: | Lydia Parrish |

| Location: | |

| Born: | |

| Died: | |

| Biography Synopsis: | Documented the ‘Shout’ tradition on the Georgia Sea Islands in the early 1940s. |

| Recording career: | |

| Most popular song(s): | |

| Musical Influences: | |

| References / links: | |

| Images: |

| Name: | Charlie Patton (how he spelled his own name, and as written on his death certificate) |

| Aka: | Charley Patton (common usage and on his gravestone), The Masked Marvel, Elder J.J. Hadley |

| Born: | 28th April 1891, Near Edwards, Hinds County, MS |

| Died: | 28th April 1934, Near Indianola, Sunflower County, MS |

| Biography Synopsis: | On June 14, 1929, Charley Patton descended into Richmond’s “Starr Valley” and stepped inside the recording studio along the railroad tracks. The man who many call “King of the Delta Blues,” the greatest of all the blues performers from Mississippi, had come to Richmond to make his own recordings for the very first time. With his guitar in hand, Patton leaned into the microphone and began to sing: “It’s a little bo weevil, she’s moving in the air, Lordy/You can plant your cotton and you won’t get half a cent, Lordy”.

Mississippi Bo Weavil Blues ignited the short (1929-34) but significant recording career of Charley Patton, who was born in 1891 on a farm between Edwards and Bolton, Mississippi. Although details of his earliest years are sketchy at best, he seems to have been born into the Chatmon family, his birth father Henderson Chatmon having sired Lonnie and Sam, of Mississippi Sheiks fame, and hokum blues specialist Bo Carter. His mother was Amy Patton, who with her husband Bill Patton and young Charley, moved to the Dockery Plantation outside Ruleville, Mississippi in 1897. It was in the communal setting at Dockery that Charley received his musical upbringing and learned and created the songs that would carry him through the rest of his life. He learned to play guitar here, and between Dockery and the Webb Jennings Plantation in the nearby town of Drew, there resided a veritable Who’s Who of blues musicians. Pioneers of the idiom such as Willie Brown, Tommy Johnson, Dick Bankston, and Roebuck “Pops” Staples (patriarch of The Staples Singers) were within easy reach during these years. In this environment, musical cross pollination was likely, and it is clear that Patton influenced them all. Son House would come down to visit from his home in the Clarksdale area, and he admits he learned from Patton. The great Howlin’ Wolf was another Dockery denizen, and took guitar lessons from Charley Patton. Wolf’s vocal style even resembles Patton’s gravel-throated rasp. Patton had a varied repertoire from which to draw by the time he left Dockery – not only blues songs, but ballads, ragtime numbers, and traditional tunes born of both black and white cultures. Bill Patton was an elder at the church on the plantation, and though by no means a religious man, Charley was schooled in spirituals. More than a mere blues singer, Charley Patton was a songster, a man who easily tapped into this diverse background, all the while creating his own songs. Throughout the early 1920s he came and went from Dockery, plying his craft around the Mississippi Delta at fish fries, dances, and jook joints, on the streets, and even at logging camps in the region. He is remembered as a great entertainer, one who delighted audiences with his “clowning,” dancing on his guitar, or playing behind his back. Patton moved to Merigold, Mississippi in 1924 and took up housekeeping with one of his common-law wives while maintaining the life of a troubadour. Five years later he left Merigold for Clarksdale and at this time came into the acquaintance of one of the most important figures in 20th century American music, H.C. Speir. Speir was a white man who ran a furniture store on Farish Street in Jackson, Mississippi. He sold Victrolas and as was the custom of the time, phonograph records to play on the machines. Because he catered to a black clientele, his market was in “race” records, which featured the blues and sanctified sounds of African-American culture of the period. More significantly, Speir scouted talent for early race labels, including many of the biggest names among blues, hillbilly, and gospel pioneers. The shape of the musical landscape we know today would be far different if not for Speir. Patton came into contact with Speir, who was impressed enough to dispatch Charley north to commit his songs to shellac. Paramount utilized Marsh Laboratories in Chicago as their recording studios, but decided to construct their own facilities in Grafton, Wisconsin, not far from company headquarters in Port Washington. During this transitional period, Paramount contracted with Gennett Records to record Paramount artists, and as a result, Charley Patton came to Richmond’s Whitewater Gorge in the late spring of 1929. Patton laid down some of his finest and best-selling sides on June 14, 1929, a total of fourteen in all. Singing along with his guitar, Charley told animated tales of bo weevil and his wife gone to wreak havoc through the land of King Cotton, and autobiographical tales of trying to keep one step ahead of the local sheriff. “When you get in trouble, there’s no use of screaming and crying…mmmmm/Tom Rushen will take you back to Cleveland a-flying,” he sang in Tom Rushen Blues, about real-life Sheriff O.T. Rushing. In Pea Vine Blues, Patton’s lyrics are about a branch of the Southern Railroad that connected Clarksdale with Greenwood, and ran through many of the towns in which he lived and traveled. Pony Blues, the first song actually released from the Richmond session (b/w Banty Rooster Blues), was a number known to Patton for many years. Charley’s hard-living lifestyle was reflected in his selection of other songs to record. The lyrics of Spoonful Blues deal with the protagonist’s willingness to kill his lover’s man over cocaine. The bawdy Shake It And Break It But Don’t Let It Fall Mama features choruses such as: “You can snatch it, you can grab it, you can break it, you can push it/Any way that a fellow can get it./I ain’t had my right mind, since I blowed in town./My jelly, my roll, please mama, don’t you let it fall”. In contrast, the remaining songs in the session were concerned with mortality and spiritual matters. Prayer of Death – in two parts – begins with a somber introduction spoken by Charley: “The Prayer Of Death. Toll the bell! Time to just toll the bell again. Tell them to sing a little song like this”. The first side contains sparse lyrics, while the second opens with lines alternately sung and spoken, then continues: “Ever since my mother’s been dead/Trouble’s been rolling all over my head/I’ve been ‘buked and I been scorned/I’ve been talked about sure as you’re born,” and after a repeat, “Hold to God’s unchanging…/Pin your hopes on things eternal.” In the final two numbers, Charley Patton seems to find even more solace in life everlasting. Lord, I’m Discouraged finds him lamenting, “Sometimes I get discouraged. I believe my work is in vain. And then, hope. But the Holy Spirit whispers, and revive my mind again.” The chorus: “There’ll be glory, what a glory when we reach that other shore./There’ll be glory, what a glory, praying to Jesus evermore./I’m on my way to glory, that happy land so fair/I’ll soon reside with God’s army, with the Saints of God up there”. Charley Patton may have seen the Light, but he continued to live hard and fast. He had a large appetite for alcohol, and troubles with the law were not uncommon. His throat was slashed badly in a 1930 altercation in Cleveland, Mississippi, from which he recovered. Around this same time in Lula, Mississippi, Charley met and “married” the last of his common-law wives, one Bertha Lee Pate, a blues singer half his age, and theirs was a tempestuous relationship. The old jailhouse still stands in Belzoni, Mississippi where Charley and Bertha Lee were both incarcerated following a particularly bad fight. Charley recounted the story in his High Sheriff Blues. Patton recorded many more records for the Paramount and Vocalion labels in the next few years, at Grafton, Wisconsin, and at studios in New York City. He was often accompanied by Son Sims on fiddle or Willie Brown on second guitar. Bertha Lee added vocals to some of the dates as well. Patton and Bertha Lee traveled to New York for what would be his final sessions on January 30th and February 1st in 1934. The couple had settled in tiny Holly Ridge, Mississippi in 1933, and by this time Charley was suffering from a heart ailment that left him chronically breathless and often drained after performances. Upon Charley’s return from the sessions in New York City, his health began to deteriorate rapidly, and he was hospitalized in Indianola, Mississippi on April 17, 1934. He died at a house at 350 Heathman Street in Indianola on April 28, 1934. He is buried next to a cotton gin in a Mississippi Delta cemetery in Holly Ridge. Charley Patton was a giant of American roots music, a major influence on his contemporaries and on the generations that followed. Performers who left the South in the Great Northern Migration carried Charley’s music to cities such as Detroit and Chicago, where it was handed down and adapted in ensuing decades. |

| Recording career: | 1929 – 1934 |

| Most popular song(s): | “Pony Blues” (1929) was included by the National Recording Preservation Board in the Library of Congress’ National Recording Registry in 2006. – Wikipedia “Mississippi Boweavil Blues”, Screamin’ and Hollerin’ The Blues”, Down The Dirt Road Blues”, “Pea Vine Blues”, “Tom Rushen Blues”, “Prayer Of Death Part 1 and 2”, “High Water Everwhere Part 1 and Part 2”. |

| Musical Influences: | Patton left indelible impressions on Son House, Howlin’ Wolf, Robert Johnson, Mississippi Fred McDowell, Muddy Waters, Bukka White, and David Honeyboy Edwards. |

| References / links: | |

| Images: |

| Name: | Sister Lottie Peavy |

| Location: | |

| Born: | |

| Died: | |

| Biography Synopsis: | |

| Recording career: | |

| Most popular song(s): | |

| Musical Influences: | |

| References / links: | |

| Images: |

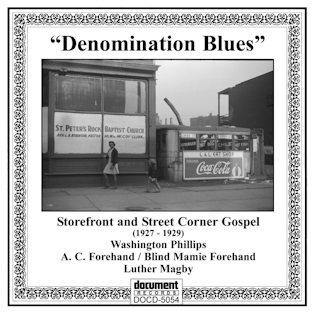

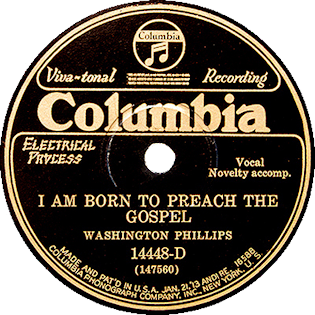

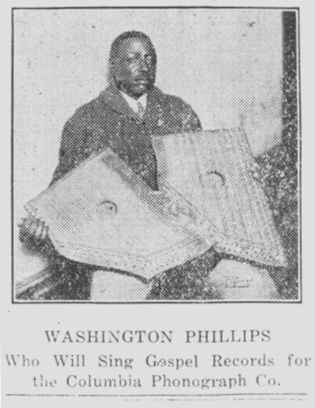

| Name: | Washington Phillips |

| Location: | Texas |

| Born: | 11th January 1880 |

| Died: | 20th September 1954 |

| Biography Synopsis: | “One of the founding fathers of American gospel music. Although his entire recorded catalogue consists of only eighteen songs, he was instrumental in laying the foundation for future performers of gospel music.”

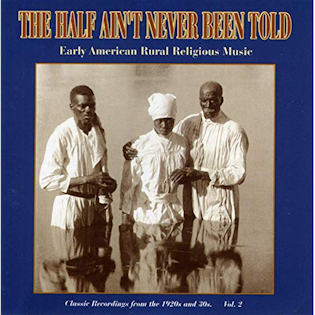

________________________________________________ George Washington “Wash” Phillips was an American gospel and gospel blues singer and instrumentalist. The exact nature of the instrument or instruments he played is uncertain, being identified only as “novelty accompaniment” on the labels of the 78rpm records released during his lifetime. He was born in Freestone County, Texas on January 11, 1880, the son of Tim Phillips (from Mississippi) and Nancy Phillips (née Cooper, from Texas). People who knew him as an adult recalled him as standing about 5 ft 8 in (1.73 m) or 5 ft 9 in (1.75 m) tall, and being “stocky” or about 180 lb (82 kg); and that he was a snuff-dipper. He farmed 30–40 acres (12–16 ha) of land by the settlement of Simsboro near Teague, Texas. He was described as a “jack-leg preacher” – i.e. someone not necessarily an ordained minister, who would attend regular services at churches hoping for an opportunity to preach, but who would more often address spontaneous gatherings in the street, or set up their own storefront churches. He was a member of Pleasant Hill Trinity Baptist Church in Simsboro, but is also known to have attended the “sanctified” St. Paul Church of God In Christ, and the St. James Methodist Church, Teague. His song “Denomination Blues” criticizes sectarianism in organized religion and hypocritical preachers. His uncomplicated and sincere faith is summarised in the last two lines of that song: It’s right to stand together, it’s wrong to stand apart, In 1927–29, he recorded 18 songs for Columbia Records in a makeshift recording studio in Dallas, Texas, under the direction of Frank B. Walker. Six of those songs were the first and second parts of three two-part songs, intended for opposite sides of one record. Four songs were unreleased at the time, and two are thought to have been lost. On September 20, 1954, he died of head injuries sustained in a fall down a flight of stairs at the welfare office in Teague. He is buried in an unmarked grave in Cotton Gin Cemetery, six miles west of Teague. His wife Marie outlived him. Some sources give his birthdate as c. 1892 and/or his date and place of death as December, 1938 in Austin State Hospital. Research has shown that that was a different Washington Phillips, the son of Houston Phillips and Emma Phillips (née Titus); he too farmed near Teague. Some sources (notably, some AllMusic entries) refer to him as “Blind Washington Phillips”. There is no suggestion in better sources that he had anything less than perfect sight. A photograph in The Louisiana Weekly of January 14, 1928 shows Phillips holding two fretless zither-like instruments. That date lies between the second and third of his five recording sessions. The instrument in his right hand has been identified as a celestaphone and that in his left as a phonoharp, both manufactured by the Phonoharp Company; in both cases with the hammer attachment missing (the instruments as sold were a type of hammered dulcimer). In the 1960s, Frank B. Walker identified Phillips’ instrument to musicologist and author Paul Oliver as a “dulceola”, saying that “nobody else on earth could use it except him”. Before a recording session, Phillips would spend half an hour or more assembling it. It has often been assumed that Walker meant a dolceola, but that cannot be so: the dolceola was manufactured, sold, and recorded commercially, and did not need assembly before use. It seems more likely that the name “dulceola” was coined specifically for unusual instruments made by Phillips himself from broken discarded ones. The aural evidence suggests Phillips strummed and plucked the strings of his instrument, and did not hammer them. Some listeners have claimed to discern differences between the instruments he used in different songs. In 2016, journalist Michael Corcoran discovered a 1907 newspaper article which reported that Phillips’ name for his instrument was a “manzarene”, and further described it as “a box about 2×3 feet, 6 inches deep, [on] which he has strung violin strings, something on the order of an autoharp. . . . He uses both hands and plays all sorts of airs.” This newly discovered name for the instrument was factored into the title of a 2016 collection of Phillips’ surviving recordings, Washington Phillips and His Manzarene Dreams. The album “Washington Phillips And His Manzarene Dreams” received two nominations for the 2018 Grammy Awards, for Best Historical Album and Best Album Notes. Source: Wikipedia |

| Recording career: | 1927-29 |

| Most popular song(s): | Mother’s Last Word to Her Son Take Your Burden to the Lord and Leave It There Paul Silas in Jail Lift Him Up That’s All Denomination Blues I Am Born to Preach the Gospel Train Your Child What Are They Doing in Heaven Today A Mother’s Last Word to Her Daughter I’ve Got the Key to the Kingdom You Can’t Stop a Tattler I Had a Good Father and Mother The Church Needs Good Deacons |

| References / links: | Washington Phillips – Storefront and Street Gospel – Document Records album notes by Guido van Rijn

Washington Phillips and His Manzarene Dreams – album review by Mike Powell Some of Us Are Haunted by Washington Phillips – album review by Amana Petrusich |

| Images: |

|

| Name: | Pilgrim Jubilee Singers |

| Location: | |

| Born: | |

| Died: | |

| Biography Synopsis: | |

| Recording career: | |

| Most popular song(s): | |

| Musical Influences: | |

| References / links: | |

| Images: |

| Name: | Price Family Sacred Singers |

| Location: | Atlanta, Georgia |

| Biography Synopsis: | Remembered as the family of Ed Price |

| Recording career: | 1927 |

| Most popular song(s): | Recorded a total of 6 songs at their single recording sessionin 1927 of which only two were released. |

| References / links: | Discography of American Historical Rcordings |

| Images: |

|

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

To help with further browsing click on the large ‘Initial’ to return to the Early Gospel Singers Introduction, or click another initial to take you to details of more early gospel singers.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Please Note:

As this is a continuously developing website, several entries only give the names with no biographical details. Please be patient as these entries are included for completeness, indicating the details are ‘coming soon’ and will be added when time allows.

If there are any early (pre war) gospel singers missing from the lists that you think should be included, please email the details to alan.white@earlygospel.com. Thank you in advance for your assistance.