A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

To help with further browsing click on the large ‘Initial’ to return to the Early Gospel Singers Introduction, or click another initial to take you to details of more early gospel singers.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

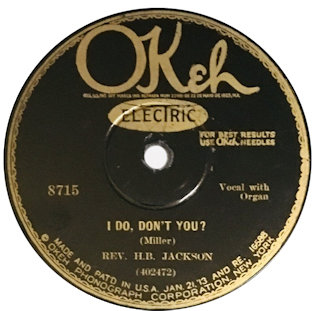

| Name: | Rev H. B. Jackson |

| Location: | ? |

| Born: | ? |

| Died: | ? |

| Biography Synopsis: | ? |

| Recording career: | 1929 |

| References / links: | Discography of American Historical Recordings |

| Images: |   |

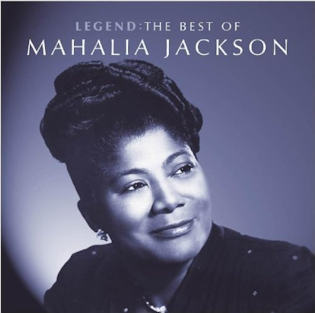

| Name: | Mahalia Jackson |

| Location: | Chicago |

| Born: | 26th October 1911 |

| Died: | 27th January 1972 |

| Biography Synopsis: | General critical consensus holds Mahalia Jackson as the greatest gospel singer ever to live; a major crossover success whose popularity extended across racial divides, she was gospel’s first superstar, and even decades after her death remains, for many listeners, a defining symbol of the music’s transcendent power. With her singularly expressive contralto, Jackson continues to inspire the generations of vocalists who follow in her wake; among the first spiritual performers to introduce elements of blues into her music, she infused gospel with a sensuality and freedom it had never before experienced, and her artistry rewrote the rules forever. Born in one of the poorest sections of New Orleans on October 26, 1911, Jackson made her debut in the children’s choir of the Plymouth Rock Baptist Church at the age of four, and within a few years was a prominent member of the Mt. Moriah Baptist’s junior choir. Raised next door to a sanctified church, she was heavily influenced by their brand of gospel, with its reliance on drums and percussion over piano; another major inspiration was the blues of Bessie Smith and Ma Rainey.

By the time she reached her mid-teens, then, Jackson’s unique vocal style was fully formed, combining the full-throated tones and propulsive rhythms of the sanctified church and the deep expressiveness of the blues with the note-bending phrasing of her Baptist upbringing. After quitting school during the eighth grade, Jackson relocated to Chicago in 1927, where she worked as a maid and laundress; within months of her arrival, she was singing leads with the choir at the Greater Salem Baptist Church, where she joined the three sons of her pastor in their group the Johnson Brothers. Although other small choir groups had cut records in the past, the Johnson Brothers might have been the first professional gospel unit ever; the first organized group to play the Chicago church circuit, they even produced a series of self-written musical dramas in which Jackson assumed the lead role. Her provocative performing style — influenced by the Southern sanctified style of keeping time with the body and distinguished by jerks and steps for physical emphasis — enraged many of the more conservative Northern preachers, but few could deny her fierce talent. After the members of the Johnson Brothers went their separate ways during the mid-’30s, Jackson began her solo career accompanied by pianist Evelyn Gay, who herself later went on to major fame as one half of gospel’s Gay Sisters. During the week, Jackson also went to beauty school, and soon opened her own salon. As her reputation as a singer grew throughout the Midwest, in 1937 she made her first recordings for Decca, becoming the first gospel artist signed to the label; curiously, none of the tracks she recorded during her May 21 session was by Thomas A. Dorsey, the legendary composer for whom she began working as a song demonstrator around that same time. (He even wrote “Peace in the Valley” with her in mind.) While her Decca single “God’s Gonna Separate the Wheat from the Tares” sold only modestly, prompting a lengthy studio hiatus, Jackson’s career continued on the upswing — she soon began performing live in cities as far away as Buffalo, New Orleans, and Birmingham, becoming famous in churches throughout the country for not only her inimitable voice but also her flirtatious stage presence and spiritual intensity. Jackson did not record again until 1946, signing with Apollo Records; although her relations with the label were often strained, the work she produced during her eight-year stay on their roster was frequently brilliant. While her first Apollo recordings, including “I Want to Rest” and “He Knows My Heart” fared poorly — so much so, in fact, that the label almost dropped her — producer Art Freeman insisted Jackson record W. Herbert Brewster’s “Move on Up a Little Higher”; released in early 1948, the single became the best-selling gospel record of all time, selling in such great quantities that stores could not even meet the demand. Virtually overnight, Jackson became a superstar; beginning in 1950, she became a regular guest on journalist Studs Terkel’s Chicago television series, and among White intellectuals and jazz critics, she acquired a major cult following based in large part on her eerie similarities to Bessie Smith. In 1952, her recording of “I Can Put My Trust in Jesus” even won a prize from the French Academy, resulting in a successful tour of Europe — her rendition of “Silent Night” even became one of the all-time best-selling records in Norway’s history. Jackson’s success soon reached such dramatic proportions that in 1954 she began hosting her own weekly radio series on CBS, the first program of its kind to broadcast the pure, sanctified gospel style over national airwaves. The show surrounded her with a supporting cast which included not only pianist Mildred Falls and organist Ralph Jones, but also a White quartet led by musical director Jack Halloran; although her performances with Halloran’s group moved Jackson far away from traditional gospel towards an odd hybrid which crossed the line into barbershop quartet singing, they proved extremely popular with White audiences, and her transformation into a true crossover star was complete. Also in 1954 she signed to Columbia, scoring a Top 40 hit with the single “Rusty Old Halo,” and two years later made her debut on The Ed Sullivan Show. However, with Jackson’s success came the inevitable backlash — purists decried her music’s turn toward more pop-friendly production, and as her fame soared, so did her asking price, so much so that by the late ’50s, virtually no Black churches could afford to pay her performance fee. A triumphant appearance at the 1958 Newport Jazz Festival solidified Jackson’s standing among critics, but her records continued moving her further away from her core audience — when an LP with Percy Faith became a smash, Columbia insisted on more recordings with orchestras and choirs; she even cut a rendition of “Guardian Angels” backed by comic Harpo Marx. In 1959, she appeared in the film Imitation of Life, and two years later sang at John F. Kennedy’s Presidential inauguration. During the ’60s, Jackson was also a confidant and supporter of Dr. Martin Luther King, and at his funeral sang his last request, “Precious Lord”; throughout the decade she was a force in the civil rights movement, but after 1968, with King and the brothers Kennedy all assassinated, she retired from the political front. At much the same time, Jackson went through a messy and very public divorce, prompting a series of heart attacks and the rapid loss of over a hundred pounds; in her last years, however, she recaptured much of her former glory, concluding her career with a farewell concert in Germany in 1971. She died January 27, 1972. Source: AllMusic.com by Jason Ankeny |

| Recording career: | 1937 – 1971 |

| Most popular song(s): | Amazing Grace

Careless Love Move On Up a Little Higher Down By The Riverside Joshua Fit The Battle of Jerico We Shall Overcome Just a Closer Walk With Thee … and many more. |

| References / links: | Mahalia Jackson Residual Family Corporation – timeline biography |

| Images: |   |

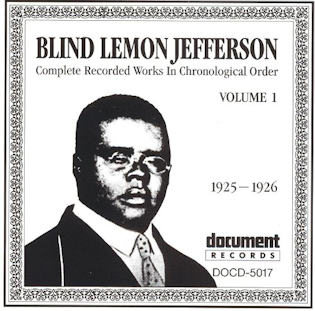

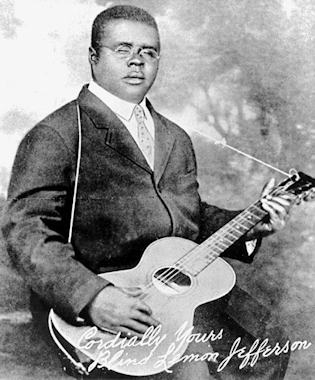

| Name: | Blind Lemon Jefferson |

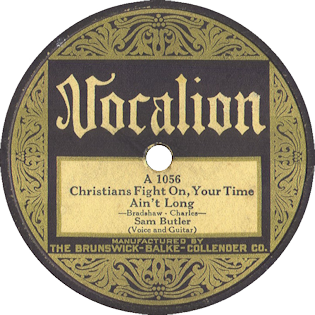

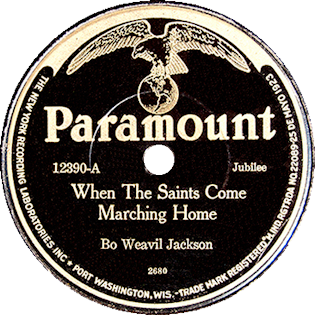

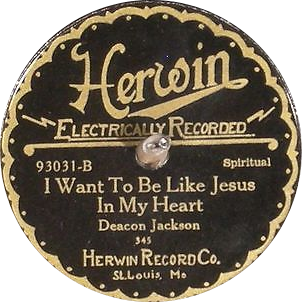

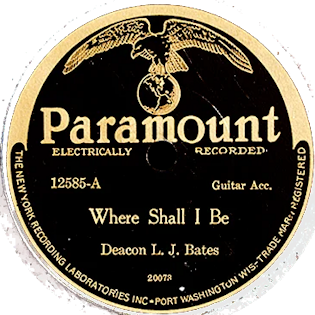

| Aka: | For his gospel songs: Deacon L. J. Bates or Deacon Jackson |

| Location: | East Texas |

| Born: | September 24, 1893 |

| Died: | December 19, 1929 |

| Biography Synopsis: | Lemon Henry “Blind Lemon” Jefferson (September 24, 1893 – December 19, 1929) was an American blues and gospel singer, songwriter, and musician. He was one of the most popular blues singers of the 1920s and has been called the “Father of the Texas Blues”.

Jefferson’s performances were distinctive because of his high-pitched voice and the originality of his guitar playing. His recordings sold well, but he was not a strong influence on younger blues singers of his generation, who could not imitate him as easily as they could other commercially successful artists. Later blues and rock and roll musicians, however, did attempt to imitate both his songs and his musical style. Jefferson was born blind, near Coutchman, Texas. He was the youngest of seven (or possibly eight) children born to Alex and Clarissa Jefferson, who were African-American sharecroppers. Disputes regarding the date of his birth derive from contradictory census records and draft registration records. By 1900, the family was farming southeast of Streetman, Texas. Jefferson’s birth date was recorded as September 1893 in the 1900 census. The 1910 census, taken in May, before his birthday, confirms his year of birth as 1893 and indicated that the family was farming northwest of Wortham, near his birthplace. In his 1917 draft registration, Jefferson gave his birthday as October 26, 1894, stating that he lived in Dallas, Texas, and had been blind since birth. In the 1920 census, he is recorded as having returned to Freestone County and was living with his half-brother, Kit Banks, on a farm between Wortham and Streetman. Jefferson began playing the guitar in his early teens and soon after he began performing at picnics and parties. He became a street musician, playing in East Texas towns in front of barbershops and on street corners. According to his cousin Alec Jefferson, quoted in the notes for Blind Lemon Jefferson, Classic Sides: “They were rough. Men were hustling women and selling bootleg and Lemon was singing for them all night… he’d start singing about eight and go on until four in the morning… mostly it would be just him sitting there and playing and singing all night”. In the early 1910s, Jefferson began traveling frequently to Dallas, where he met and played with the blues musician Lead Belly. Jefferson was one of the earliest and most prominent figures in the blues movement developing in the Deep Ellum section of Dallas. It is likely that he moved to Deep Ellum on a more permanent basis by 1917, where he met Aaron Thibeaux Walker, also known as T-Bone Walker. Jefferson taught Walker the basics of playing blues guitar in exchange for Walker’s occasional services as a guide. By the early 1920s, Jefferson was earning enough money for his musical performances to support a wife and, possibly, a child. However, firm evidence of his marriage and children has not been found. Prior to Jefferson, few artists had recorded solo voice and blues guitar, the first of which were the vocalist Sara Martin and the guitarist Sylvester Weaver, who recorded “Longing for Daddy Blues”, probably on October 24, 1923. The first self-accompanied solo performer of a self-composed blues song was Lee Morse, whose “Mail Man Blues” was recorded on October 7, 1924. Jefferson’s music is uninhibited and represented the classic sounds of everyday life, from a honky-tonk to a country picnic, to street corner blues, to work in the burgeoning oil fields (a reflection of his interest in mechanical objects and processes). Jefferson did what few had ever done before him – he became a successful solo guitarist and male vocalist in the commercial recording world. Unlike many artists who were “discovered” and recorded in their normal venues, Jefferson was taken to Chicago, Illinois, in December 1925 or January 1926 to record his first tracks. Uncharacteristically, his first two recordings from this session were gospel songs (“I Want to Be Like Jesus in My Heart” and “All I Want Is That Pure Religion”), released under the name Deacon L. J. Bates. A second recording session was held in March 1926. His first releases under his own name, “Booster Blues” and “Dry Southern Blues”, were hits. Their popularity led to the release of the other two songs from that session, “Got the Blues” and “Long Lonesome Blues”, which became a runaway success, with sales in six figures. He recorded about 100 tracks between 1926 and 1929; 43 records were issued, all but one for Paramount Records. Paramount’s studio techniques and quality were poor, and the recordings were released with poor sound quality. In May 1926, Paramount re-recorded Jefferson performing his hits “Got the Blues” and “Long Lonesome Blues” in the superior facilities at Marsh Laboratories, and subsequent releases used those versions. Both versions appear on compilation albums. Largely because of the popularity of artists such as Jefferson and his contemporaries Blind Blake and Ma Rainey, Paramount became the leading recording company for the blues in the 1920s. Jefferson’s earnings reputedly enabled him to buy a car and employ chauffeurs (this information has been disputed); he was given a Ford car “worth over $700” by Mayo Williams, Paramount’s connection with the black community. This was a common compensation for recording rights in that market. Jefferson is known to have done an unusual amount of traveling for the time in the American South, which is reflected in the difficulty of placing his music in a single regional category. Jefferson’s “old-fashioned” sound and confident musicianship made it easy to market him. His skillful guitar playing and impressive vocal range opened the door for a new generation of male solo blues performers, such as Furry Lewis, Charlie Patton, and Barbecue Bob. He stuck to no musical conventions, varying his riffs and rhythm and singing complex and expressive lyrics in a manner exceptional at the time for a “simple country blues singer.” According to the North Carolina musician Walter Davis, Jefferson played on the streets in Johnson City, Tennessee, during the early 1920s, at which time Davis and the entertainer Clarence Greene learned the art of blues guitar. Jefferson was reputedly unhappy with his royalties (although Williams said that Jefferson had a bank account containing as much as $1500). In 1927, when Williams moved to OKeh Records, he took Jefferson with him, and OKeh quickly recorded and released Jefferson’s “Matchbox Blues”, backed with “Black Snake Moan”. It was his only OKeh recording, probably because of contractual obligations with Paramount. Jefferson’s two songs released on OKeh have considerably better sound quality than his Paramount records at the time. When he returned to Paramount a few months later, “Matchbox Blues” had already become such a hit that Paramount re-recorded and released two new versions, with the producer Arthur Laibly. In 1927, Jefferson recorded another of his classic songs, the haunting “See That My Grave Is Kept Clean” (again using the pseudonym Deacon L. J. Bates), and two other uncharacteristically spiritual songs, “He Arose from the Dead” and “Where Shall I Be”. “See That My Grave Is Kept Clean” was so successful that it was re-recorded and re-released in 1928. Jefferson died in Chicago at 10:00 a.m. on December 19, 1929, of what his death certificate said was “probably acute myocarditis”. For many years, rumors circulated that a jealous lover had poisoned his coffee, but a more likely explanation is that he died of a heart attack after becoming disoriented during a snowstorm. Some have said that he died of a heart attack after being attacked by a dog in the middle of the night. In his 1983 book Tolbert’s Texas, Frank X. Tolbert claims that he was killed while being robbed of a large royalty payment, by a guide escorting him to Chicago Union Station to catch a train home to Texas. Paramount Records paid for the return of his body to Texas by train, accompanied by the pianist William Ezell. Jefferson was buried at Wortham Negro Cemetery (later Wortham Black Cemetery). His grave was unmarked until 1967, when a Texas historical marker was erected in the general area of his plot, however the precise location of the grave is unknown. By 1996, the cemetery and marker were in poor condition, and a new granite headstone was erected in 1997. The inscription reads: “Lord, it’s one kind favour I’ll ask of you, see that my grave is kept clean.” The words come from the lyrics of his own song, “See That My Grave Is Kept Clean”. In 2007, the cemetery’s name was changed to Blind Lemon Memorial Cemetery, and his gravesite is kept clean by a cemetery committee in Wortham. Jefferson had an intricate and fast style of guitar playing and a particularly high-pitched voice. He was a founder of the Texas blues sound and an important influence on other blues singers and guitarists, including Lead Belly and Lightnin’ Hopkins. He was the author of many songs covered by later musicians, including the classic “See That My Grave Is Kept Clean”. Another of his songs, “Matchbox Blues”, was recorded more than 30 years later by the Beatles, in a rockabilly version credited to Carl Perkins, who did not credit Jefferson on his 1955 recording. The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame selected Jefferson’s 1927 recording of “Matchbox Blues” as one of the 500 songs that shaped rock and roll. Jefferson was among the inaugural class of blues musicians inducted into the Blues Hall of Fame in 1980. Source: Wikipedia |

| Recording career: | 1900 – 1929 |

| Images: |

|

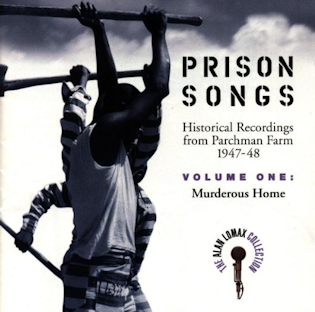

| Name: | Jimpson & Gang |

| Aka: | Henry Wallace |

| Location: | Parchman Farm (Mississippi State Penitentiary) |

| Born: | ? |

| Died: | ? |

| Biography Synopsis: | “While researching Parchman, I came across an album of songs from the 1947-1948 recording sessions that had been released in 1997. All of the music was wonderful, but one song haunted me: Jimpson’s rendition of “No More, My Lord.” Jimpson isn’t exactly as well known as Lead Belly, but you may have heard his voice without realizing it. A version of “Murderer’s Home,” sung by Jimpson, is featured on the Gangs of New York soundtrack. … “No More, My Lord,” is a fantastic song in its own right, but what I really love is a moment specific to the second recording that Lomax made. Most of the way through the two minute track, the usual axe-stroke beat is followed by syncopation: two unexpected strikes. During the song, Jimpson is actually chopping wood. The surprising percussion is a wood chip striking Lomax’s microphone and rebounding off of it.”

– ‘Alan Lomax at Parchman Farm’ blog entry by Jasper Frank |

| Recording career: | 1947-1948 |

| Most popular song(s): | Murderer’s Home

No More, My Lord |

| Musical Influences: | Parchman Farm! |

| References / links: | Alan Lomax at Parchman Farm |

| Images: |   |

| Name: | P. C. Johnson and his Singers |

| Location: | |

| Biography Synopsis: | ? |

| Recording career: | ? |

| Most popular song(s): | |

| References / links: | |

| Images: |  |

| Name: | Bessie Johnson’s Sanctified Singers |

| Aka: | Memphis Sanctified Singers – see entry under ‘M’ |

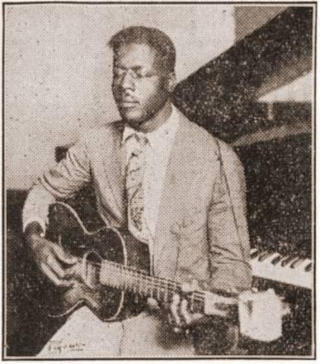

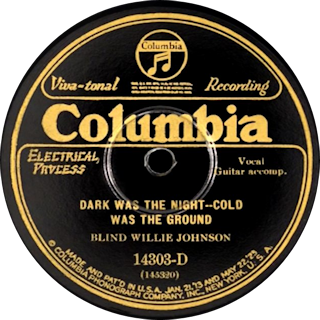

| Name: | Blind Willie Johnson |

| Location: | Dallas, Texas |

| Born: | 25th January 1897 |

| Died: | 18th September 1945 |

| Biography Synopsis: | Blind Willie Johnson was an American gospel blues singer and guitarist and evangelist. His landmark recordings completed between 1927 and 1930 – thirty songs in total – display a combination of powerful “chest voice” singing, slide guitar skills, and originality that has influenced later generations of musicians. Even though Johnson’s records sold well, as a street performer and preacher he had little wealth in his lifetime. His life was poorly documented, but over time music historians such as Samuel Charters have uncovered more about Johnson and his five recording sessions. Johnson is credited as one of the most influential practitioners of the blues, and his slide guitar playing, particularly on his hymn “Dark Was the Night, Cold Was the Ground”, is highly acclaimed.

Johnson was born on January 25, 1897, in Pendleton, Texas, a small town near Waco, to sharecropper George Johnson (also identified as Willie Johnson Sr.) and his wife, Mary Fields, who died in 1901. His family, which according to the blues historian Steven Calt included at least one younger brother named Carl, moved to the agriculturally rich community of Marlin, where Johnson spent most of his childhood. There, the Johnson family attended church – most likely the Marlin Missionary Baptist Church – every Sunday, a practice which had a lasting impact on Johnson and fueled his desire to be ordained as a Baptist minister. When Johnson was five years old, his father gave him his first instrument – a cigar box guitar. Johnson was not born blind, though he was impaired with the disability at an early age. It is uncertain how he lost his sight, but it is generally agreed by most biographers of Johnson that he was blinded by his stepmother when he was seven years old, a claim that was first made by Johnson’s purported widow Angeline Johnson. In her recollection, Willie’s father had violently confronted Willie’s stepmother about her infidelity, and during the argument she splashed Willie with a caustic solution of lye water, permanently blinding him. Other theories have also been developed to explain Johnson’s visual impairment, including that he wore the wrong spectacles, that he viewed a partial solar eclipse that was observable over Texas in 1905 or a combination of the two conjectures. Few other details are known about the singer’s childhood. At some point he met another blind musician, Madkin Butler, who had a powerful singing and preaching style that influenced Johnson’s own vocal delivery and repertoire. Adam Booker, a blind minister interviewed by the blues historian Samuel Charters in the 1950s, recalled that while visiting his father in Hearne, Johnson would perform religious songs on street corners with a tin cup tied to the neck of his Stella guitar to collect money. Occasionally, Johnson would play on the same street as Blind Lemon Jefferson, but the extent of the two songsters’ involvement with each other is unknown. In 1926 or early 1927, Johnson established an unregistered marriage with Willie B. Harris, who occasionally sang on the street with him and at benefits for the Marlin Church of God in Christ with Johnson accompanied on piano. From the relationship, Johnson had a daughter, Sam Faye Johnson Kelly, in 1931. The blues guitarist L. C. Robinson recalled that his sister Anne also claimed to have been married to Johnson in the late 1920s. By the time Johnson began his recording career, he was a well-known evangelist with a “remarkable technique and a wide range of songs”, as noted by the blues historian Paul Oliver. On December 3, 1927, Johnson was assembled along with Billiken Johnson and Coley Jones at a temporary studio that talent scout Frank Buckley Walker had set up in the Deep Ellum neighborhood in Dallas to record for Columbia Records. In the ensuing session, Johnson played six selections, 13 takes in total, and was accompanied by Willie B. Harris on his first recording, “I Know His Blood Can Make Me Whole”. Among the other songs Johnson recorded in Dallas were “Jesus Make Up My Dying Bed”, “It’s Nobody’s Fault but Mine”, “Mother’s Children Have a Hard Time”, “Dark Was the Night, Cold Was the Ground”, and “If I Had My Way I’d Tear the Building Down”. He was compensated with $50 per “usable” side – a substantial amount for the period – and a bonus to forfeit royalties from sales of the records. The first songs to be released were “I Know His Blood Can Make Me Whole” and “Jesus Make Up My Dying Bed”, on Columbia’s popular 14000 Race series. Johnson’s debut became a substantial success, as 9,400 copies were pressed, more than the latest release by one of Columbia’s most established stars, Bessie Smith, and an additional pressing of 6,000 copies followed. His fifth recorded song, “Dark Was the Night, Cold Was the Ground”, eventually the B-side of Johnson’s second release, best exemplifies his unique guitar playing in open D tuning for slide. For the session, Johnson substituted a knife or penknife for the bottleneck and – according to Harris – he played with a thumb pick. His melancholy, indecipherable humming of the guitar part creates the impression of “unison moaning”, a style of singing hymns that is common in southern African-American church choirs. In 1928, the blues critic Edward Abbe Niles praised Johnson in his column for The Bookman, emphasizing his “violent, tortured, and abysmal shouts and groans, and his inspired guitar playing”. Johnson, accompanied by Harris, returned to Dallas on December 5, 1928, to record “I’m Gonna Run to the City of Refuge”, “Jesus Is Coming Soon”, “Lord I Just Can’t Keep From Crying”, and “Keep Your Lamp Trimmed and Burning”. Two unreleased and untitled tracks were also recorded by Johnson under the pseudonym Blind Texas Marlin, but the master tapes of the session have never been recovered. Another year passed before Johnson recorded again, on December 10 and 11, 1929, the longest sessions of his career. He completed ten sides in 16 takes at Werlein’s Music Store in New Orleans, also recording some duets with an unknown female singer, who is thought to have been a member of Reverend J. M. Gates’s congregation, according to Johnson’s biographer D. N. Blakey. The blind street performer Dave Ross reported observing Johnson performing on the street in New Orleans in December 1929. According to a story heard by the jazz historian Richard Allen, Johnson was arrested while performing in front of the Custom House on Canal Street, for allegedly attempting to incite a riot with his impassioned rendition of “If I Had My Way I’d Tear the Building Down”. For his fifth and final recording session, Johnson journeyed to Atlanta, Georgia, with Harris returning to provide vocal harmonies. Ten selections were completed on April 20, 1930. “Everybody Ought to Treat a Stranger Right” paired with “Go with Me to That Land” were chosen as the first single released from the session. However, the Great Depression had wiped out much of Johnson’s audience, and consequently only 800 copies were pressed. Some of his songs were re-released by Vocalion Records in 1932, but Johnson never recorded again. Johnson allegedly remarried, this time to Angeline Johnson, in the early 1930s, but, as with Harris, it is unlikely that the union was officially registered. Throughout the Great Depression and the 1940s, he performed in several cities and towns in Texas, including Beaumont. A city directory shows that in 1945, a Reverend W. J. Johnson – undoubtedly Blind Willie – operated the House of Prayer at 1440 Forrest Street, in Beaumont. In 1945, his home was destroyed by a fire, but, with nowhere else to go, Johnson continued to live in the ruins of his house, where he was exposed to the humidity. He contracted malarial fever, and no hospital would admit him, either because of his visual impairment, as Angeline Johnson stated in an interview with Charters, or because he was black. Over the course of the year, his condition steadily worsened until he died, on September 18, 1945. His death certificate reported syphilis and blindness as contributing factors. According to his death certificate, he was buried in Blanchette Cemetery, in Beaumont. The location of the cemetery had been forgotten until it was rediscovered in 2009. His grave site remains unknown, but the researchers who identified the cemetery erected a monument there in his honor in 2010. – Wikipedia |

| Recording career: | 1927-1930 |

| Most popular song(s): | “Dark Was the Night, Cold Was the Ground”

“It’s Nobody’s Fault But Mine” “If I Had My Way I’d Tear The Building Down.” |

| References / links: | Wikipedia – Blind Willie Johnson

No Depression – “Dark Was The Night: The LIfe and Times of Blind Willie Johnson” |

| Images: |

|

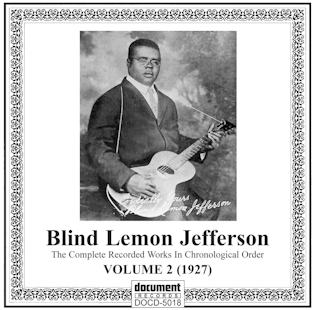

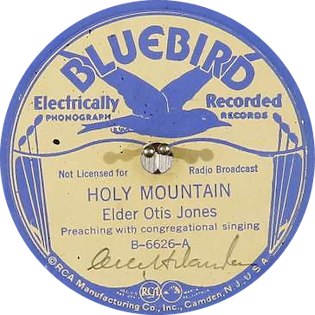

| Name: | Prof. Johnson & His Gospel Singers |

| Location: | |

| Born: | |

| Died: | |

| Biography Synopsis: | ? |

| Recording career: | |

| Most popular song(s): | |

| Musical Influences: | |

| References / links: | |

| Images: |

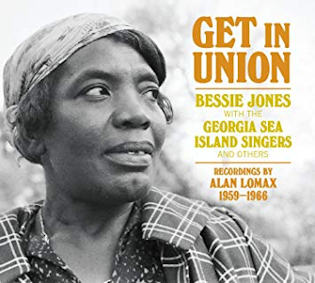

| Name: | Bessie Jones and the Sea Island Singers |

| Location: | South Sea Islands |

| Born: | 8th February 1902 |

| Died: | 17th July 1984 |

| Biography Synopsis: | Mary Elizabeth “Bessie” Jones was an American gospel and folk singer credited with helping to bring folk songs, games and stories to wider audiences in the 20th Century. Alan Lomax, who first encountered Jones on a field recording trip in 1959, said, “She was on fire to teach America. In my heart, I call her the Mother Courage of American Black traditions.”

Jones grew up in an impoverished but musical family in the small black farming community of Dawson, Georgia. Her grandfather, a former slave born in Africa, taught her many songs he would sing in the fields. Jones only attended school until age 10, and she had her first child and marriage at just 12 years old. Her first husband, Cassius, died away a few years later. In 1924, Jones left her 10-year-old daughter with relatives and traveled to Florida, where she worked odd jobs, played cards and sold moonshine. She eventually settled down with her second husband on St. Simons Island, where she joined the Georgia Sea Island Singers. Jones felt a need to preserve African-American history history through song and dance, and in 1961 she traveled to New York City so Lomax could record her biography and body of music. The recordings are preserved in the Alan Lomax archive. She and the Georgia Sea Island Singers toured extensively in the 1960s, singing in Carnegie Hall, Central Park, the Smithsonian Institution’s folklife festivals and the Newport Folk Festival. She was awarded many of folk music’s premiere honors, including National Endowment for the Arts National Heritage Fellowship and the Duke Ellington Fellowship at Yale University. Jones told an interviewer in Alachua, Florida in the early 1980s, that she was born in Lacrosse, Florida (Alachua County), when that area was a tung oil production area, but this claim is dismissed by researchers Bob Eagle and Eric LeBlanc. Jones also said she had not been to a doctor since 1925 and that she wore many copper bracelets which protected her from disease.[citation needed] She died from leukemia in 1984. Jones’ 1960 song “Sometimes” was sampled in American electronica musician Moby’s 1998 single “Honey”. Source: Wikipedia |

| Recording career: | |

| References / links: | National Endowment for the Arts – 1982 NEA National Heritage Fellow |

| Images: |   |

| Name: | Jones Brothers Trio |

| Location: | |

| Born: | |

| Died: | |

| Biography Synopsis: | ? |

| Recording career: | |

| Most popular song(s): | |

| Musical Influences: | |

| References / links: | |

| Images: |  |

| Name: | The Jubilee Four |

| Aka: | See also ‘The Shields Brothers’ |

| Location: | Cleveland, Ohio |

| Biography Synopsis: | The Jubilee Four were a group of two sets of brothers and a neighbour who began singing together in Cleveland, Ohio in the 1930s until three members of the group were drafted to serve in World War II. The group comprised: Clifford Phelps, William Phelps, Eugene Ross, Johnny Shields and Claude Shields, Jr. Three members still sing today under the name of the Shields Brothers. |

| Recording career: | |

| Most popular song(s): | |

| Musical Influences: | |

| References / links: | ‘Cleveland’s Gospel Music’, Frederick Burton, Arcadia Publishing 2003 |

| Images: |

| Name: | The Jubilee Gospel Team |

| Location: | |

| Biography Synopsis: | See Rev. B.J. Hill entry |

| Recording career: | |

| Most popular song(s): | |

| Musical Influences: | |

| References / links: | |

| Images: |

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

To help with further browsing click on the large ‘Initial’ to return to the Early Gospel Singers Introduction, or click another initial to take you to details of more early gospel singers.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Please Note:

As this is a continuously developing website, several entries only give the names with no biographical details. Please be patient as these entries are included for completeness, indicating the details are ‘coming soon’ and will be added when time allows.

If there are any early (pre war) gospel singers missing from the lists that you think should be included, please email the details to alan.white@earlygospel.com. Thank you in advance for your assistance.