A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

To help with further browsing click on the large ‘Initial’ to return to the Early Gospel Singers Introduction, or click another initial to take you to details of more early gospel singers.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

| Name: | Ward Singers |

| Location: | Philadelphia |

| Biography Synopsis: | In 1931, seven-year-old Clara Ward and her nine-year-old sister Willarene (better known as “Willa”) began performing with their mother, Gertrude, in Philadelphia. Gertrude first called the group “The Consecrated Gospel Singers,” then simply “The Ward Trio.” The three singers, with the two girls alternating as piano accompanists, initially appeared at churches in and around their hometown, but after creating a sensation at the National Baptist Convention in Chicago in 1943, they began touring widely. In 1949, having expanded the lineup to include singers Henrietta Waddy and Marion Williams, the group traveled to Los Angeles and cut their first records for the Miltone label. Curiously, none of the songs they recorded in Los Angeles were ever issued on Miltone, but many soon appeared on other labels, including Dolphin’s of Hollywood, Gotham and Savoy.

By 1950, the Ward Singers were the hottest female gospel group in the land. Two of their songs—Surely God Is Able and Move Up a Little Higher, both released by Gotham that year—became major gospel hits, said to have sold more than a million copies each. Gotham billed them as “The Famous Ward Singers (of Philadelphia)” and the name stuck, albeit without the name of the city. The group also recorded over the years as “Clara Ward and the Ward Singers.” Clara’s distinctive arrangement of the traditional hymn How I Got Over, recorded in 1950 for Gotham, was soon successfully covered by Mahalia Jackson for Apollo Records in New York. It became Jackson’s signature song. By 1951, the group was formally recording for Savoy and continued doing so for the next 11 years. Other singles and albums also appeared during that period on such labels as Duke, Dot and Vanguard. Later recordings were issued on Columbia, Verve, Philips and Nashboro until Clara’s death in 1973 at age 48. “With Clara as lead singer and arranger, the Famous Ward Singers not only defined the female Gospel sound but set about establishing the demeanor of the female group in performance,” gospel historian Horace Clarence Boyer wrote in his forward to Willa Ward’s 1997 book How I Got Over: Clara Ward and the World-Famous Ward Singers. “They walked into an auditorium or church straight and proud like movie stars. . . . In the early days they wore regular church robes but soon adopted elegant suits or dresses, which quickly gave way to elaborate sequined evening gowns. To complete their dramatic image, they often wore coiffured wigs. . . .” Unhappy with the low pay they were receiving from the group’s manager, Gertrude Ward, Waddy, Williams, Frances Steadman, Kitty Parham and Esther Ford quit the group in 1958. Together they formed the Stars of Faith, who recorded albums for Savoy and Vee-Jay before Williams left in 1965 to launch a solo career. Gertrude had no trouble finding new members for the Ward Singers, however. The Ward Singers had been queens of the gospel circuit during the 1950s, but by the early ’60s they had found a new, largely white, and more lucrative mainstream audience for their show-stopping stage act and flamboyant attire, losing much of their African American church followers in the process. Such lively numbers as Down By the Riverside and When the Saints Go Marching In replaced many of the earlier gospel hits in their repertoire as they performed on major television network shows, in nightclubs and Las Vegas hotels and at Disneyland. They even toured for six weeks as an opening act for comedian Jack Benny. Clara Ward was influenced early in life by gospel singers Queen C. Anderson and Clara “The Georgia Peach” Hudman. In turn, she greatly influenced the young Aretha Franklin, with whose father, the Reverend C.L. Franklin, the Ward Singers frequently toured during the 1950s. Miami-born Marion Williams (1927–1994) also influenced well-known musicians, particularly gospel great Alex Bradford and rock ’n’ roll pioneer Little Richard, both of whom emulated her high-pitched “woos.” —Lee Hildebrand |

| Recording career: | 1931-1972 |

| Most popular song(s): | How I Got Over |

| Musical Influences: | Queen C. Anderson and Clara “The Georgia Peach” Hudman |

| References / links: | Wikipedia |

| Images: |

|

| Name: | Rev. Charles White |

| Location: | |

| Born: | |

| Died: | |

| Biography Synopsis: | |

| Recording career: | |

| Most popular song(s): | How Long |

| Musical Influences: | |

| References / links: | |

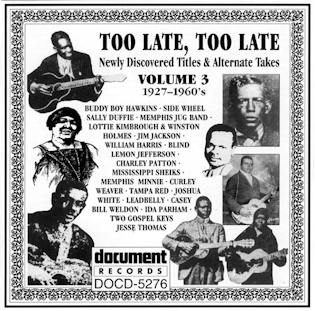

| Images: |  |

| Name: | Washington White |

| Aka: | Pseudonym for Bukka White |

| Born: | November 12, 1906 |

| Died: | February 26, 1977 |

| Biography Synopsis: | Booker T. (Taliaferro) Washington “Bukka” White was an African-American Delta blues guitarist and singer. Bukka is a phonetic spelling of White’s first name; he was named after the well-known African-American educator and civil rights activist Booker T. Washington.

White was born south of Houston, Mississippi. He was a first cousin of B.B. King’s mother (White’s mother and King’s grandmother were sisters). He played National resonator guitars, typically with a slide, in an open tuning. He was one of the few, along with Skip James, to use a crossnote tuning in E minor, which he may have learned, as James did, from Henry Stuckey. He also played piano, but less adeptly. White started his career playing the fiddle at square dances. He claimed to have met Charlie Patton soon after, but some have doubted this recollection. Nonetheless, Patton was a strong influence on White. “I wants to come to be a great man like Charlie Patton”, White told his friends. He first recorded for Victor Records in 1930. His recordings for Victor, like those of many other bluesmen, included country blues and gospel music. Victor published his photograph in 1930. His gospel songs were done in the style of Blind Willie Johnson, with a female singer accentuating the last phrase of each line. From fourteen recordings, Victor released two records under the name Washington White, two gospel songs with Memphis Minnie on backing vocals and two country blues. Nine years later, while serving time for assault, he recorded for the folklorist John Lomax. The few songs he recorded around this time became his most well known: “Shake ‘Em On Down,” and “Po’ Boy.” His 1937 version of the oft-recorded song “Shake ‘Em on Down,” is considered definitive; it became a hit while White was serving time in Mississippi State Penitentiary, commonly known as Parchman Farm. He wrote about his experience there in “Parchman Farm Blues”, which was released in 1940. Bob Dylan covered his song “Fixin’ to Die Blues”, which aided a “rediscovery” of White in 1963 by guitarist John Fahey and Ed Denson, which propelled him into the folk revival of the 1960s. White had recorded the song simply because his other songs had not particularly impressed the Victor record producer. It was a studio composition of which White had thought little until it re-emerged thirty years later. Fahey and Denson found White easily enough: Fahey wrote a letter to White and addressed it to “Bukka White (Old Blues Singer), c/o General Delivery, Aberdeen, Mississippi”—presuming, given White’s song “Aberdeen, Mississippi”, that White still lived there or nearby. The postcard was forwarded to Memphis, Tennessee, where White worked in a tank factory. Fahey and Denson soon traveled there to meet him, and White and Fahey remained friends for the rest of White’s life. He recorded a new album for Denson and Fahey’s Takoma Records, and Denson became his manager. White was at one time also managed by Arne Brogger, an experienced manager of blues musicians. Later in his life, White was friends with the musician Furry Lewis. The two were recorded (mostly in Lewis’s Memphis apartment) by Bob West for an album, Furry Lewis, Bukka White & Friends: Party! At Home released on the Arcola label. White died of cancer in February 1977, at the age of 67 or 70, in Memphis, Tennessee. In 1990 he was posthumously inducted into the Blues Hall of Fame (along with Blind Blake and Lonnie Johnson). On November 21, 2011, the Recording Academy announced the addition of “Fixin’ to Die Blues” to its 2012 list of Grammy Hall of Fame Award recipients. Source: Wikipedia |

| Recording career: | 1930 – 1940 |

| Most popular song(s): | Blues: “Shake ‘Em On Down, “Po’ Boy”, “Parchman Farm Blues”.

Gospel: “The Promise True and Grand”, “I Am In THe Heavenly Way”. |

| Musical Influences: | His gospel songs were done in the style of Blind Willie Johnson, with a female singer accentuating the last phrase of each line. |

| Images: |   |

| Name: | Rev. Robert Wilkins |

| Location: | Memphis and north MIssissippi |

| Born: | January 16, 1896 |

| Died: | May 26, 1987 |

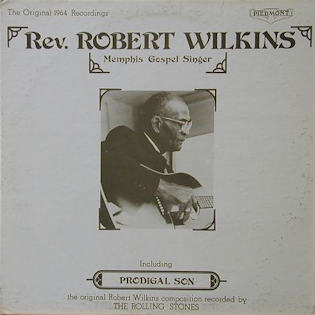

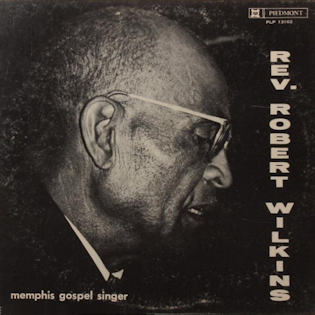

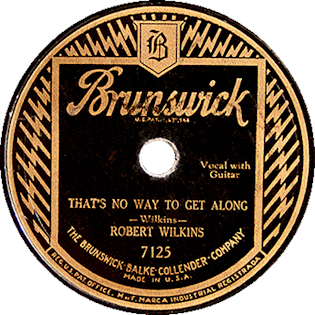

| Biography Synopsis: | Robert Timothy Wilkins was an American country blues guitarist and vocalist, of African-American and Cherokee descent. His distinction was his versatility: he could play ragtime, blues, minstrel songs, and gospel music with equal facility.

Wilkins was born in Hernando, Mississippi, 21 miles from Memphis. He performed in Memphis and north Mississippi during the 1920s and early 1930s, the same time as Furry Lewis, Memphis Minnie (whom he claimed to have tutored), and Son House. He also organized a jug band to capitalize on the “jug band craze” then in vogue. Though never attaining success comparable to that of the Memphis Jug Band, Wilkins reinforced his local popularity with a 1927 appearance on a Memphis radio station. From 1928 to 1936 he recorded for Victor and Brunswick Records, alone or with a single accompanist, like Sleepy John Estes, and unlike Gus Cannon of Cannon’s Jug Stompers. He sometimes performed as Tom Wilkins or as Tim Oliver (his stepfather’s name). In 1936, at the age of 40, he quit playing the blues and joined the church after witnessing a murder where he performed. In 1950 he was ordained. In 1964 Wilkins was “rediscovered” by blues revival enthusiasts Dick and Louisa Spottswood, making appearances at folk festivals and recording his gospel blues for a new audience. These include the 1964 Newport Folk Festival; his performance of “Prodigal Son” there was included on the Vanguard Records album Blues at Newport, Volume 2. In 1964 he also recorded his first full album, Rev. Robert Wilkins: Memphis Gospel Singer, for Piedmont Records. Another full session, recorded live at the 1969 Memphis Country Blues Festival, was released in 1993 as “…Remember Me”. Wilkins died on May 26, 1987, in Memphis, Tennessee, at the age of 91. His son, Reverend John Wilkins, continues his father’s gospel blues legacy **. His best-known songs are “That’s No Way to Get Along” and his reworked gospel version, “The Prodigal Son” (which was covered under that title by the Rolling Stones), “Rolling Stone”, and “Old Jim Canan’s”. The Stones were forced to credit “The Prodigal Son” to Wilkins after lawyers approached the band and asked for the credit to be changed. Early pressings of Beggars Banquet credited only Mick Jagger and Keith Richards as composers, not Wilkins. Source: Wikipedia ** See also my interview with Rev. John Wilkins on www.earlyblues.com |

| Recording career: | 1928 – 1964 |

| Most popular song(s): | “That’s No Way to Get Along” / “The Prodigal Son” |

| Images: |

|

| Name: | Rev. P. M. Williams |

| Location: | |

| Born: | |

| Died: | |

| Biography Synopsis: | |

| Recording career: | |

| Most popular song(s): | |

| Musical Influences: | |

| References / links: | |

| Images: |

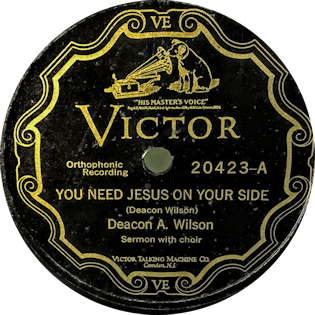

| Name: | Deacon A. Wilson |

| Location: | ? |

| Born: | ? |

| Died: | ? |

| Biography Synopsis: | ? |

| Recording career: | 1926 |

| Most popular song(s): | You Need Jesus On Your Side

Certainly Lord |

| References / links: | Discography of American Historical Recordings |

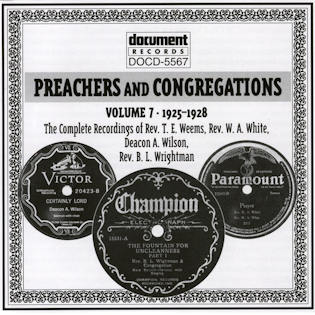

| Images: |   |

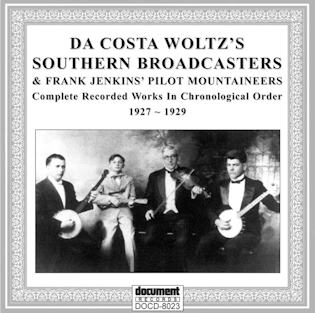

| Name: | Da Costa Woltz’s Southern Broadcasters |

| Biography Synopsis: | DaCosta Woltz was an American old time banjo player from Galax, Virginia. His band, DaCosta Woltz’s Southern Broadcasters played Appalachian old-time string band and square dance music and recorded in the late 1920s. Ben Jarrell, of Surrey County, North Carolina, and father of influential fiddle and banjo musician Tommy Jarrell, played with the Southern Broadcasters. DaCosta Woltz was a promoter of patent medicine, the mayor of Galax, and a first-rate banjo player.

Source: Wikipedia In 1927, Da Costa Woltz — mayor of Galax, VA, and a promoter of patent medicines — got together a string band of local musicians for a three-day recording session in Richmond, IN. Billing themselves somewhat cumbersomely as Da Costa Woltz’s Southern Broadcasters, the group featured Frank Jenkins on banjo and sometimes fiddle, Woltz on second banjo, Ben Jarrell on fiddle, and a 12-year-old Price Goodson on ukulele and harmonica; the young Goodson presumably functioned as much as a novelty and gimmick as a musician, performing on only three of the sides. Of the 18 pieces recorded, only one actually included the entire ensemble: the remaining tracks featured members of the group broken down into solos, duets, and trios. Such variation of personnel amounted to a fair degree of diversity within the overall output, offering a mix of instrumental music and old-time Southern melodies (mostly sentimental ditties along the lines of “Take Me Back to the Sweet Sunny South”). The recording session particularly served as a vehicle for Jenkins’ precise, quick-trickling banjo playing and for Jarrell’s raspy fiddling and vocals, perhaps the most unifying element of the sides. Despite the group’s name, the Southern Broadcasters never actually ventured into radio broadcasting , nor did they, despite their abilities on the 18 tracks cut in Richmond, return to the recording studio. Of the group, only Jenkins recorded again, joined in 1929 by his son Oscar and the prolific Ernest Stoneman under the name of Frank Jenkins’ Pilot Mountaineers. The musical legacy of the Broadcasters did at least survive, meanwhile, through the bloodlines of some of the original outfit’s members: More than three decades after the Pilot Mountaineers session, banjoist Oscar Jenkins returned to recording in the 1960s and ’70s, while Jarrell’s son Tommy was one of the most emulated fiddlers of that era’s old-time revival. Source: AllMusic.com |

| Recording career: | 1927 for Gennett and related labels |

| Most popular song(s): | Gospel: “Are you Washed in the Blood of the Lamb” |

| References / links: | |

| Images: |   |

| Name: | Rev. S. J. “Steamboat Bill” Worell |

| Location: | Harlem, NY |

| Born: | ? |

| Died: | ? |

| Biography Synopsis: |

Source: DOCD 5406 LIner Notes |

| Recording career: | 1926 – 1927 |

| Most popular song(s): | ? |

| Images: |   |

| Name: | Rev. B. L. Wrightman |

| Location: | |

| Born: | |

| Died: | |

| Biography Synopsis: | |

| Recording career: | |

| Most popular song(s): | |

| Musical Influences: | |

| References / links: | |

| Images: |

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

To help with further browsing click on the large ‘Initial’ to return to the Early Gospel Singers Introduction, or click another initial to take you to details of more early gospel singers.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Please Note:

As this is a continuously developing website, several entries only give the names with no biographical details. Please be patient as these entries are included for completeness, indicating the details are ‘coming soon’ and will be added when time allows.

If there are any early (pre war) gospel singers missing from the lists that you think should be included, please email the details to alan.white@earlygospel.com. Thank you in advance for your assistance.