Essays & Articles

“Gon’ Act Like A Preacher, Ride From Town to Town”* (*= Matchbox Blues, Blind Lemon Jefferson,1927)

(a brief survey of black preachers in the South-before 1940)

by ‘Mississippi’ Max Haymes

This article is an initial ‘testing the water’ on a subject in earlier African American song which has rarely been considered in print up to this point in time – the preacher in the late 19th. and early 20th. centuries. The contributions in Saints & Sinners edited by Robert Sacre (1996) and the essential Songsters & Saints by Paul Oliver (1984) are the most important exceptions. Together with the notes to the 7-CD series Preachers And Congregations (DOCD-5529, 5530, 5547, 5548, 5559, 5560, 5567), nine volumes of the Rev. J. M. Gates (DOCD-5414, 5432, 5433, 5442, 5449, 5457, 5469, 5483, 5484) and various others in Document’s awesome reissue programme including individual preachers on their own CD, they amount to practically all the sources we have on this genre. [The excellent 6xCD set “Goodbye Babylon” (Dust To Digital DTD-01) includes on the sixth disc pre-war black preachers complete with transcriptions and biblical sources; and in great sound. The other five CDs cover both black and white gospel songs from the early 1900s to the 1950s and the set is an invaluable research tool for historians.]

I have chosen a line as my title from the seminal blues singer from East Texas, Blind Lemon Jefferson (c.1893-1929) because I see black gospel as the flipside of the blues coin which featured pre-war blues – along with other blues historians. I shall be covering this aspect a little later on – albeit briefly. Blind Lemon of course commenced his recording career at the end of 1925 with two gospel songs as ‘Deacon L. J. Bates’.

Although intended as a larger work (possibly a book) I will here, be concentrating mainly on the origins of rap together with some early background to the importance of the preacher in early black communities; especially from the blues and gospel vantage point. I will also be considering a particular theme which gets tangled up with the well-known ‘Dry Bones In The Valley’, much-recorded in the pre-war era by black preachers and quartets alike.

Part I

Origins of Rap

The origins of rap go back to the black (and some white?) preachers of the 19th. and early 20th. centuries in the Southern states. But these preachers were themselves drawing on a far older tradition. “Rhetoric as a subject as well as an art originated in Sicily in the fifth century BC, and was developed in Athens and in Asia Minor, before becoming an accepted study in Rome.” (1). Kamm goes on to describe this phenomenon “There were basically three branches of oratory: the display of one’s art, often in the form of a panegyric [‘Panegyric’ refers to praise or a eulogy “A laudatory speech”. (2)] or invective (the latter had its counterpart in the medieval Scottish flyting); the persuasion of an audience to a point of view; and the defense or prosecution of a defendant in a court of law. Each of these involved five separate skills: selection of content; arrangement; language; memory; delivery.” (3). In fact, all the qualities required by a black preacher if he/she were to be successful in communicating with their congregation. This was to be the bane of whites, especially the plantation owners of a large number of slaves, in the antebellum era. Generally outnumbered by blacks in many parts of the South, they lived in an almost perpetual fear of a slave revolt (which was sometimes realized). And the black preacher was one of the main reasons for this.

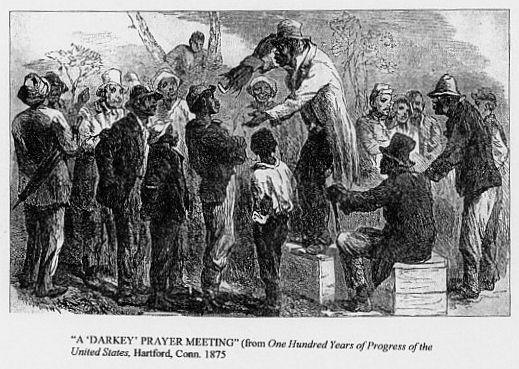

However, this phenomenon did not appear much before the mid-eighteenth century and ‘The Great Awakening’. It should be remembered that for the first 200 years or so since the initial black indentured servants were landed at Jamestown, Virginia, (in 1619) there was little appetite or indeed teaching of Christianity either to servants, slaves or plantation owners. “During most of the colonial period white Southerners were practicing Anglicans, nominal Anglicans, or nothing. Few slaves embraced Christianity in any form before the 1790s.” (4) The plantation owners were highly suspicious of the few early white preachers who traveled the South in the 1750s, be they Presbyterian, Baptist or Methodist. They could be attempting to undermine the ‘peculiar institution’, (as the slavery system was referred to by abolitionists) by sowing the seeds of discontent and rebellion in the minds of the slave congregations. But this first Great Awakening was somewhat sporadic and quite localized to particular areas. However, it laid down the foundations for the ‘Second’ Great Awakening at the turn of the 19th. century. Boles describes this “more accurately the South’s first great awakening. It changed the religious landscape of the region, ensuring a Protestant evangelical dominance that continues today.” (5) During this period in the early 1800s because of the thousands of people who flocked to hear itinerant white preachers the camp meeting came into being. [Although there were many black preachers, these would generally be confined to the plantations in the slavery period prior to camp meetings].

People would literally take tents (or make a crude one) and camp out at these meetings for days at a time. While some would return home after a short stay the camp meeting could last for a couple of weeks or more. Especially popular “in the border states of Kentucky and Tennessee” these events attracted huge crowds and sometimes “as many as 20,000 or more at events such as the one held at Cane Ridge, Ky., [which] included black as well as well as white worshipers.” (6).

Although not popular in the Northeast, the camp meeting was a huge success in the South. “Many black ministers were inspired to preach at such gatherings, though at first only to other blacks, and a characteristic oral style of delivery emerged from this experience.” (7). Thus setting the scene for black preachers after the Civil War and into the 20th. century, separating from the white dominated religion and starting up churches specifically for the black community. The African Methodist Episcopalian (AME) and the Church Of God in Christ (COGIC) for example.

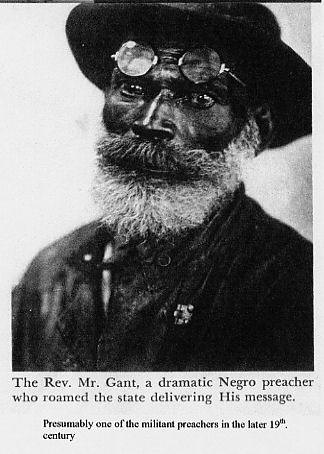

After the Civil War in 1865, white fears of the power of black preachers in the South seemed to be at least partially realized. “…black-controlled churches and preachers not responsible to the master would become principal influences in the lives of the freedmen. Much as the whites had feared, rumours and reports of what transpired in the black churches suggested not only emotional extravagance but political subversion. In Mobile, Alabama, for example, several black preachers were accused of inculcating the freedmen with doctrines of murder, arson, violence, and hatred of white people”. (8). A Southern white historian, Thomas Owen, writing in 1920 related: “In the Reconstruction Era [1867-1877] the presence of Federal troops merely served to aggravate the ill-feeling and increase lawlessness, particularly when they were negro troops. The negro preachers, whose number greatly increased during the first few years after the War, were one of the most disturbing elements. They had great influence with their own race, and almost always exerted it to arouse animosity among the negroes [sic] community toward the southern whites and a disinclination to work.”(9)

After the Civil War in 1865, white fears of the power of black preachers in the South seemed to be at least partially realized. “…black-controlled churches and preachers not responsible to the master would become principal influences in the lives of the freedmen. Much as the whites had feared, rumours and reports of what transpired in the black churches suggested not only emotional extravagance but political subversion. In Mobile, Alabama, for example, several black preachers were accused of inculcating the freedmen with doctrines of murder, arson, violence, and hatred of white people”. (8). A Southern white historian, Thomas Owen, writing in 1920 related: “In the Reconstruction Era [1867-1877] the presence of Federal troops merely served to aggravate the ill-feeling and increase lawlessness, particularly when they were negro troops. The negro preachers, whose number greatly increased during the first few years after the War, were one of the most disturbing elements. They had great influence with their own race, and almost always exerted it to arouse animosity among the negroes [sic] community toward the southern whites and a disinclination to work.”(9)

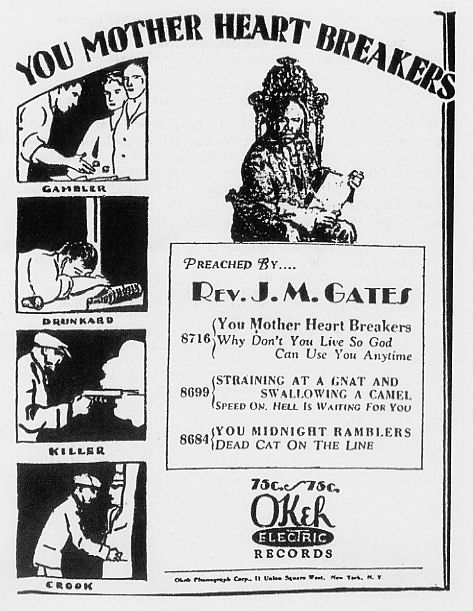

By the time the post-Reconstruction era (1877-1900s) had effectively ‘re-enslaved’ the black community in agricultural bondage, (sharecropping) the convict-lease system and the ‘separate but equal’ decision handed down by the U.S. Federal Government in 1896, the black population (mostly still in the South) had been compelled to relinquish the right of freedom of speech for fear of white reprisals (sometimes fatal). By then blacks had been ‘legally’ stripped of their constitutional right to vote and the preachers had to also adapt accordingly if they were to survive. In the 1920s black preachers first appeared on recordings in the fledgling ‘race’ market. One of the most prolific of all in this genre was Reverend J.M. Gates. “Born c.1884” he had been “the pastor of Mount Calvary Baptist Church in Rock Dale Park, Atlanta, since 1914 (and held the post until he died around 1941)” (10). [Although more recently in 2003 David Evans claims that Gates “died in 1945”. (11)].

Gates was also one of the most popular of the early recorded preachers and one particular ‘mini-sermon’, accompanied by Deacon Leon Davis and either Sister Jordan or Sister Norman who give spoken/shouted encouragement, almost uniquely attacks the white society under the guise of directing his anger at the much-maligned (justifiably) Prohibition Act/Volstead Act which came into effect at the start of 1920.

Punctuating his rap with exhalations of breath ‘uh-huh’ and utterances of ‘well’, well’, ‘tell the truth’, and ‘’preach it to me, Gates’, from his congregation; Rev. Gates delivers the ‘real message’, protest at racial injustice from whites and ends his sermon delivered in a fierce a tone as he generally got with the last words “a camel” contrasting in a higher, clearer voice; which is half-sung and half-spoken.

Ah, I want to speak to you people from this subject. (Amen)

Since now we have a mixed congregation. (Alright. Yes!)

‘Strainin’ At A Gnat (Uh-huh) An’ Swallowin’ A Camel’.

(God Almighty. Lord, have mercy!)

Uh-we are livin’ in a age. (Yeh! Uh-huh)

Where we haven’t got time. (Praise God)

Strainin’ at a gnat (Mm-mm) an’ swallowin’ a camel.

(Mm-mm. Yes, that is true)

Our lives is so much like a gnat. (Yeh! Uh-uh)

Uh-until we can’t tell (Yeh!) what time we’re gonna die. (Great God!)

Why, they tell me (Uh-huh) – that in the mornin’. (Yeh!)

At six o’clock (Yes, sir!) a gnat is un-hatched in an egg. (God Almighty!)

An’ at nine o’clock he’s a baby gnat. (O.K.)

An’ at twelve o’clock he’s a young man. (Yes, sir! Alright)

An’ at three o’clock he’s an old man, then. (Oh, yeah! Alright)

An’ at six o’clock he die of the old age. (Well. Praise God) Well, you see we haven’t got long (Haven’t got long) to live in this world

(Well, well)

So why strain at a gnat (Come on! Come on!) an’ swallow a camel?

(Great God! Yes, sir)

You people (Uh-huh) that’s tryin’ to win the whole world. (Well!)

An’ lose your soul. (Alright! Come on!)

You straining at a gnat (Alright! Yes, sir!) an’ swallowin’ a camel.

(Great God!)

You, (You!) you Negro-haters. (Alright. Yes!)

You, that can’t sit with him on the street car. (Come on! Come on!)

You, that can’t eat-uh-at the same table with him.

(Well, well, well. Praise God!)

You. (Come on!) I’m talkin’ about you. (Pretty soon)

You, that can’t sit in your own automobile with him. (Well!)

Uh-I’ll tell you what you can do. (Well. Come on! Come on!)

You can eat what they cook. (Yeh! You can)

You can sleep in their bed. (Tell the truth!)

You can let them drive your car. (Well!)

While you sit in the rear. (Talk to me)

Uh-an’ he have your life in his hands. (Yes, sir!)

You strainin’ (Well, well. Preach to me) at a gnat an’ swallowing a camel.

(Alright!)

Mmm! (Talk with me). You straining at a gnat an’ swallowin’ a camel.

(Yeh! Alright)

You can’t drink with him. (No!)

But you can buy what he has to drink. (Alright!)

When I say ‘what ‘e has to drink’, I’m talkin’ about what you thinkin’ ‘bout.

(Alright. Yessir!)

Now, I saw- (Come on! Come on!) –uh-where the Government’s spending 20

million dollars [to] stop men from drinkin’ what they-uh-make. (Yeh!)

Uhhh! (Moan children) I tell you, you are strainin’ at a gnat tryin’ to swallow

the camel (Well)

Prohibition law (Alright) I’m talkin’ about. (Yeh!)

Has caused many men (Well) to become cold-blooded murderers.

(Talk with me)

An’ have left this country full of widows (Preach!) an’ orphans. (Yeh!)

An’ remind me (Preach it to me Gates) of goin’ to the War. (Talk to me)

It’s-uh-rich man’s war. (Yeh! Well)

But a poor man’s fight. (Yeh!)

Straining at a gnat (Well) an’ swallowin’ a camel.

(Talk to me. Come on! Come on!)

I’m talkin’ to you. (Well. Come on!)

You can’t risk your children to church. (Yes!)

Uh-at night. (Well)

Well, they go to the theater. (Alright!)

Straining at a gnat (Preach to me!) an’ swallowin’ a camel. (Alright! Well) (12)

OKeh publicity ad. 21 Sept 1929

Although the actual language is far removed from the 19th. century preachers, nevertheless Rev. J.M. Gates succeeds in delivering his ‘sermon’ with carefully controlled anger and intensity with emotional support from his small studio congregation becoming an almost tangible part of the whole.

Said Litwack of these earlier preachers, not only were whites described in their sermons as “white devils”, “demons”, or “pro-slavery devils”, but they talked of an impending race war in which the whites would be exterminated. “He [the black preacher] frequently cried out ‘In this hour of blood who will stand by me? And his question ever met with most enthusiastic replies of ‘I will, bless God!’ from the assembled auditory.” (13). Because of the increasingly powerless position that blacks found themselves in by the beginnings of the 20th. century, these preachers had to resort to symbolism and different levels of meaning in their texts – an ancient West African tradition in their own songs. So with reference to the ‘call to arms’ just quoted we should surely consider the almost unearthly beauty of Hattie Parker’s soprano solo in the Pace Jubilee Singers’ ‘Stand By Me’ [Victor 21551] in a more encompassing light.

When the storm of life is raging, stand by me.

When the storm of life is raging, stand by me.

(Stand by me) (x 2)

When the world is tossing me like a ship up on the sea;

Thou who ruleth the wind and water, stand by me.

(Stand by me)

In the midst of faults and failure, stand by me.

(Stand by me) (x 2)

When I do the best I can, an’ my friends all understand;

Thou will knowest all about me, stand by me.

(Stand by me)

In the midst of persecution, stand by me. (x 2)

(Stand by me)

When my foe is battle [a]rray, undertake to stop [by] my way;

Thou who saved Paul and Silas, stand by me.

(Stand by me) (14)

Heilbut who calls this ‘mournful gospel’ which is so prevalent in earlier styles, dubbed it “the Baptist blues” (15). Some of Parker’s words could easily be adapted to a more vengeful situation, and indeed war is expected ‘when my foe is battle ‘rray’ [sic]. Intriguingly, Heilbut who quotes the composer of ‘Stand By Me’ (C.A. Tindley) as it appeared in 1905; [A “famous delta ballad writer”, an African American Charles Haffer, claimed to have written this song in 1909; which he titled ‘Stand By Me When I Cross the Jordan River’ which he heard “at a [church] convention-a’sociation” [sic] (16) “But when I went home I wrote it entirely different. It just come to me through the spirit…” (17). But Tindley’s song had been extant some 4 years at this point and as Heilbut says was “Tindley’s greatest composition…” (18) It is quite likely Haffer might have heard it at the church convention he had just left. What is also intriguing is that in 1939 his interviewer, Alan Lomax, surely knew the song but was obviously unaware that Tindley had composed it]. shows this earlier text where the word ‘foe’ is in the plural. Did Hattie Parker singularize it to imply the white man? Something akin to the transformation of a chorus in another Tindley composition occurs in:

“I’ll overcome, I’ll overcome, I’ll overcome someday,

If in my life I do not yield, I’ll overcome some day.”

Which Heilbut quotes and points out was easily changed “into the greatest of all freedom songs. Thousands of Southern blacks were raised on ‘I’ll Overcome’ a sentiment one step away from militant protest.” (19) A direct if modified link with the latter-day black preachers’ sermons.

If the preacher was an important part of the black community in the antebellum era, by the 1870s he/she had become the focal point for the religious section and indeed also influenced others who were more of a secular bent. Litwack illustrates: “With the withdrawal of thousands of blacks from the white-dominated churches the black church became the central and unifying institution in the postwar black community. For more than any newspaper convention, or political organization, the minister communicated directly and regularly with his constituents and helped to shape their lives in freedom. Not only did he preach the gospel to the masses in these years but he helped to politicize and educate them. Many of the black missionaries and clergymen also assumed the position of teachers, and very often the classrooms themselves were housed in the only available quarters in town – the church.” (20). One of the most famous of the early quartets, the Norfolk Jazz/Jubilee Quartet, called on the people to come to the church service:

Brothers an’ sisters. (Heyyy-heyyy)

Sisters an’ Misters.(Heyyy-heyyy)

Good people, one an’ all.

Come on down an’ join the congregation at the;

Old Town Hall.

Jim Johnson is the preacher (Heyyy-heyyy)

He is your teacher. (Heyyy-heyyy) (21)

The Norfolks were inspired by a female quartet who recorded the song some five years earlier. To the “wondrously archaic sound…[which] still maintains its ability to mesmerize listeners” (22), the Virginia Female Jubilee Singers handed out a similar invitation:

| (spoken) | 1st. female: | “Listen to this sisters”. |

| 2nd.female: | “What is it?” | |

| 1st.female: | “There’s gonna be a great camp meetin’”. | |

| 3rd.female: | “Where?” | |

| 1st.female: | “Right here in this town”. | |

| 3rd. & 4th. | “Hallelujah!” | |

| (in unison) | ||

| (sung) | Brothers an’ sisters, | |

| Sisters an’ Misters; | ||

| Good people, one and all. | ||

| Come on down an’ join the congregation; | ||

| At the old Town Hall. | ||

| Brother Johnson the preacher | ||

| He am your teacher; | ||

| Learnin’ every word he says. | ||

| Don’t be slow, | ||

| Come let’s go; | ||

| This am Revival Day.” (23) |

Famous blues/folk singer Leadbelly would incorporate the teacher theme into what he called ‘a children’s play song’ for the Bluebird label in 1940 with vibrant 12-string guitar.

| Sittin’ at school, at school, at school, boy; | |

| Sittin’ at school to save my soul. | |

| Obey the rules, the rules, the rules, boy; | |

| That’s [what] I was told. | |

| Chorus: | Ha-ha this-away; |

| Ha-ha that -away. | |

| Ha-ha this-away; | |

| It ain’t no sin. | |

| Went to a teacher, teacher, teacher; | |

| Teacher was a preacher, preacher, preacher; | |

| Teacher was a preacher so I was told. | |

| Chorus: | Ha-ha this-away, etc. (24) |

Also a children’s ‘ring song’ according to Leadbelly, who cut four versions of this title between 1935 and 1941.

Rev. W.M. Mosley from the Mississippi Delta delegated his tutorial role to parents of young ‘upstarts’. He had a much harder approach to his preaching than Rev. J.M. Gates, even when he’s more laid-back as he is here. What Paul Oliver aptly called one of “the straining preachers”. Mosley half chants and half speaks as he commences; with encouragement as always from his congregation in the recording studio.

I want to talk to you young girls, you know, here tonight.

(Amen/Aright!)

A special subject. (God Almighty!/Lord, have mercy!)

An’ this subject is this. (Yes!)

A wonderful counsellor. (Oh! Yes, Lord!)

He’s a wonderful counselor. (Yeah!)

An’ if you take his instruction. (Yeah! Well)

You will be alright. (Yes, man!)

I tell you what. (Yeah! Uh-huh)

Some of you girls. (Yeah!)

You’re so mean. (Oh! Yes)

Until you won’t hear. (Alright!)

Even Mama. (Alright!)

When she calls you. (Well)

Some of you told me. (Yeah!)

I talkin’ about you. (Yeah!)

Fourteen. (Well)

An’ fifteen. (Well!)

An’ sixteen. (Yeah!)

Talkin’ about you upstarts. (Have mercy!)

You young folk. (Yeah!)

Oh! Lord! (Yeah! Oh, well!)

You folks. (Yeah!)

Gotta be so sharp. (Yeah!/Well!)…(25)

Mosley’s rasping voice raps out a sentence ‘chopped up’ by the responses of the congregation. So that it becomes extended to five separate lines: “Some of you girls/you’re so mean/until you won’t hear/even Mama/when she calls you.”. After denouncing the girls for being “expert dancers” and young men for taking them out of their mother’s homes to pimp for them when they become ‘street walkers’, he exhorts them “If you will obey your parents” via the word of God:

If you. (Preach, man!)

Were to accept. (Well!)/Come on, come on!)

The counsel. (Pray to God)

Of my Lord. (Amen!)

Everything. (Yes!)

Will be alright. (Yessir!)…(26)

Rev. W.M. Mosley’s subject appears to be unique – so far! Although in the previous year of 1929, Rev D.C. Rice had recorded ‘Who Do You Call That Wonderful Counsellor’ [Vocalion 1462] he does not target teenage girls for criticism. [Rev. D.C. Rice had recorded ‘Jesus Christ The Wonderful Counsellor’ at the previous session in July, 1929, for Vocalion but remains unissued. Because of its close proximity to Vocalion 1462 it can reasonably be assumed to be another version of this recording]. Indeed, Rice does not preach on this side, and in fact included far less sermonising in his entire output of some 30 titles made between 1928 and 1930; than many other black preachers.

Another straining preacher, Rev. E.S. ‘Shy’ Moore, delivered a fine, hoarse rapping style on his ‘Christ The Teacher’ [Victor 21737] in 1928 as one side of his only issued recording. Not all pre-war recorded sermons were unaccompanied. As David Evans noted “Besides jug bands, one hears slide guitar, ragtime piano and jazz combos…” (27) Moore’s ‘Christ The Teacher’ [the only version listed in B. & G.R.] is a case in point. The three unidentified musicians accompany him on guitar, piano, and jug. A possible line-up could have been Elijah Avery on guitar, Gus Cannon jug, and Jab Jones playing piano. Both Cannon and Avery, as part of Cannon’s Jug Stompers, were in Victor’s Memphis studio just two days prior to the Moore session. And the Memphis Jug Band pianist Jab Jones had been in the same studio [with the MJB] eight days earlier on 15th. September. But this highly speculative on my part and it is much more likely “that they were church musicians.” (28)

But one of the truly classic examples of the ‘origins of rap’ must surely be Rev. Isaiah Shelton’s ‘The Liar’ [Victor 20583] in 1927. Possibly inspired by a 1926 recording by Rev. Edward Clayborn, ‘the Guitar Evangelist’, Shelton punches out the rhythm with a gravelly vocal-cum-chant. Often punctuating some of his words with the suffix ‘a’ or a shouted emphasis. The whole bearing a remarkable resemblance to one of the pioneers of soul music in the 1950s. [A very simplified definition of soul music, which didn’t really develop until the 1960s, is a singer taking the harsh and raucous, rapping styles of early black preachers and substituting secular lyrics to replace the sermon. Also see the magnificent Library of Congress recording by Bozie Sturdivant: ‘Ain’t No Grave Can Hold My Body Down’ from 1942 – arguably the first “soul” record?]. David Evans wrote: “The refrain of this traditional song, which Rev. Shelton sings only twice, was adapted by Ray Charles in 1956 to create a substantial secular hit, ‘Leave My Woman Alone’ ! (29) This was more in the black r n’ b vein which had been evolving since the mid-1940s but it ‘fits’ the definition listed below in the footnote.

Rev. Shelton (preaching/rapping)

Just let me tell you what a liar will do-a.

He’s always coming with something new. Yeh-yeh.

Steal your heart there with false pretension.

Makin’ out like-a he’s your bosom friend.

Ehhhh! When ‘e finds out you believe what ‘e say.

Then that old liar gon’ have his way-a.

He’ll bring you news-a from women an’ men-a.

He’ll make you fall out-a with dearest friend.

Ehhh! When a liar gets a notion to bend an’ prove [i.e. the truth]

Well, he lay round the neighborhood getting’ news.

A littler further on he introduces the chorus which is taken up by two or three female singers who finish the lines:

If you don’t want to –get in trouble,

If you don’t want (everybody!) to get in trouble;

Well, if you don’t want (sing!) to get in trouble.

Better let that liar alone. (30)

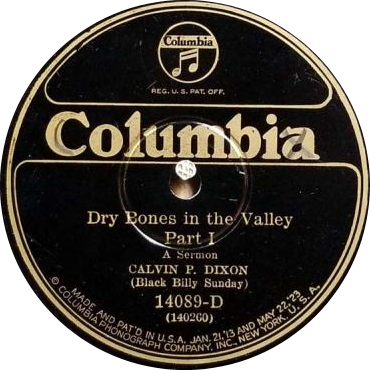

The style and sound of many preachers was perhaps surprisingly quite varied. Ranging from the growling ‘straining’ variety which also included Rev. T.E. Weems (who cut a version of “The Liar’ in November, 1927) Rev. A.W. Nix, and Rev J.C. Burnett; through higher and more clear sounds of Rev. J. M. Milton and Rev. Jim Beal; to the semi-spoken chanting of a Rev. Emmett Dickinson, Rev. H.R. Tomlin or Rev. Sutton E. Griggs . Eugene Genovese in his essential Roll Jordan Roll says quite rightly “No doubt the style of the black preachers in slavery times differed from the style of rural black preachers today; no doubt it would be an error to read the one back into the other. Yet the evidence suggests far greater continuity than discontinuity, and much can be learned about the antebellum preachers by following the accounts of today’s black “folk preachers” in the studies by Bruce A. Rosenberg and the Reverend H. Mitchell. [The Art Of The American Folk Preacher. Bruce Rosenberg. Oxford University Press. New York. 1970. And Black Preaching Henry H. Mitchell. J.P. Lippincott Co. Philadelphia & New York. 1970]. Their preaching has a strong element of chanting-virtually of singing.” (31). Perhaps we should take a closer look at the myriad of recorded black preachers in the 1920s and ‘30s for some pointers to an ‘earlier’ style. “What the recordings could provide, as no other medium could, was the opportunity to hear, and to hear again, the words spoken by the preacher and the responses of his congregation” (32) Not surprisingly, the very first preacher to record, in 1925, could well be the link between old and ‘new’; Calvin P. Dixon.

Part II

Dry Bones In The Valley

Dixon, also known as ‘Black Billy Sunday’, but is not the Paramount artist of that name, recorded 10 sides between 14th. and 16th. January in 1925 – all in New York City. Fortunately, Columbia issued all but two of them. His recorded legacy could well be a rare glimpse of an earlier preaching style going back into the 19th. century – and beyond? Unusual in not using the abbreviated title ‘Rev.’ on his records might indicate his status as a ‘jack-leg’ preacher (i.e. one who is not ordained in church). This of course does not affect the power of the preacher’s conviction.

Dixon, also known as ‘Black Billy Sunday’, but is not the Paramount artist of that name, recorded 10 sides between 14th. and 16th. January in 1925 – all in New York City. Fortunately, Columbia issued all but two of them. His recorded legacy could well be a rare glimpse of an earlier preaching style going back into the 19th. century – and beyond? Unusual in not using the abbreviated title ‘Rev.’ on his records might indicate his status as a ‘jack-leg’ preacher (i.e. one who is not ordained in church). This of course does not affect the power of the preacher’s conviction.

Notwithstanding comments from well-respected blues/gospel historians such as Ken Romanowski, Paul Oliver and Kip Lornell (as ‘Christopher Lornell’). Romanowski referred to Dixon’s “dignified and measured preaching” while allowing that “his recordings document a preaching style that was not often recorded again in the prewar period once the discs by more emotionally charged preachers came into vogue”. (33). Oliver stated that “Preaching was present in Dixon’s records but of music there was little in his voice and of frenzy there was none.” (34). While Lornell said “Calvin P. Dixon…was quite subdued though adamant.” (35).

But this does not tell the complete story or illustrate a full picture of the qualities of the sermons of Calvin P. Dixon. Having said that, the eight recorded sides that have come down to us still leave much in the fog of history. As many preachers in the early days were often semi-literate and relied on their memory to quote biblical texts, there were errors in those quotations. I intend to combine a short study of Dixon with one such error in his opening remarks on his remarkable two-part “Dry Bones In The Valley” [Columbia 14089-D] from his third and final session in mid-January, 1925.

But first let me explain how I arrived at this point. It really started when I was reading the notes to a Document CD (DOCD-5519) featuring the Jubilee Gospel Team and Deep River Plantation Singers. One of the Jubilee titles was ‘Dry Bones In The Valley’ [QRS R7013] from their first session in 1928, and Chris Smith noted that this song “is almost a stream-of-consciousness monologue; the story of a woman murdered by her 12 lovers is said to be Biblical, but I cannot trace it.” (36). The picture became a bit clearer when I got the Dixon tracks included in the unique ‘Preachers & Congregations’ series, also on Document. Yet although he greatly extended the picture, which it transpires the Jubilee Gospel Team drew on almost exclusively, his 1925 version does not give us the location via biblical reference as to where he got his text. In fact, after a brief introduction to Part 1 which does indeed come from Ezekiel, as Dixon says; he then quotes from a different book in the Bible! Dixon referred to “a certain Levite” in this first part and this had me hurrying to Leviticus (Old Testament) which I vaguely thought would be the link. But although there are some references citing aspects of adultery, illegal/immoral sex, etc. there was still no mention of a murdered woman and her twelve lovers.

Then quite by chance I came across a recent publication entitled ‘Women In The Bible’ by John Baldock. As the sub-title included ‘Bloodlust And Jealousy’, I promptly bought it. And all is revealed – well, nearly all! Baldock includes a section under the heading ‘The Levite’s Concubine’. And the reference from the Bible is actually the Book Of Judges. Baldock lists “Judges 19:1-20: 6” (37) A dark and dastardly tale unfolds which shows God to urge bloody wars between the Israelites and Benjamites (two of the tribes of Israel). And from Judges (as Baldock oddly omits this section) it appears that God ‘fixes’ the Benjamites to make sure the Israelis win! [Judges 20:28]

Basically, a “certain Levite from the hill country of Ephraim took as a concubine (or second wife) [While considering the story of Hagar [see Genesis], an African American interpretation on biblical passages; notes: “The term used here for wife (ishshah) has a broad meaning. Elsewhere, it is used as ‘concubine’ (Judg. 19:1,17) and ‘harlot’ (e.g. Joshua 2:1; 6:22; Judg. 11:11)” ](39) “a young woman from Bethlehem in Judah”. (38) After a row she left the Levite and went back to her father’s home in Bethlehem. After a period of four months (!) the Levite goes looking for her and is greeted warmly by her father. The latter persuades the Levite to stay for several days until on the evening of the fifth he insists they must get back home – that is to say, with his concubine.

They reached Jerusalem on the way back to Ephraim, arriving in the evening when the sun was going down. Rejecting his servant’s suggestion to stay overnight in Jerusalem, the Levite refused saying “We will not turn off into a foreign town whose inhabitants are not Israelites. We will go to Gibeah” (40). They arrived at Gibeah as the sun was going down, once more. This town was one belonging to the Benjamites and as such not much more of a desirable stopping place than Jerusalem – even though they were ‘a fellow tribe’. Exhausted after yet another full day’s travel on a donkey, the Levite decided to stop in Gibeah even if that meant sleeping in the central square! Fortunately, [or not as it turned out] a ‘townie’ from Ephraim came by and insisted that the Levite, his concubine, male servant and two donkeys should stay at his house; right there in Gibeah.

Later that night a bunch of hooligans/ruffians banged on the front door demanding the Levite to come out so they could have sex with him! The old man who had taken him in begged the ruffians not to “…do such a wicked thing. Since this man is my guest, do not do this to him. Take my daughter instead. She is a virgin. I will bring her out, and you can do with her as you wish, but do not commit such an act against this man”. (41) A blatant example of hypocrisy and sexism at its evil height! In Judges the Levite’s concubine is also offered at this time. The ruffians ‘certain sons of Belial’ [Judges 19:22] grabbed the concubine and repeatedly raped her and sexually abused her all night long. Calvin P. Dixon related:

(preaching)

When they arrived in the city, there was an old man who saw them

wandering up an’ down the street.

An’ insisted upon them to come an’ remain with him o’er night.

They accepted of his invitation.

And while they were on their way to the home, they met twelve men

who knew this woman.

And they followed behind them until they arrived at their destiny. [sic]

Twelve o’clock in the night, they came to the home where they was residing;

An’ commanded this man to bring this woman out to them.

He refused an’ pled for their protection.

And offered his two daughters instead.

They wouldn’t hear him as they beat down the door.

Took his wife out by force.

They carried her off on the outskirts of the city.

They assaulted her an’ left her for dead. (42)

Momentarily departing from his text Dixon rightly condemns this horrendous act.

Any man who would criminally [sexually] assault a defenceless woman;

Ought to be killed before sunrise. (43)

Around day break the poor woman had managed to drag herself back to the old man’s front door. On discovering her later in the morning (!) the Levite shouted to her to get up as they were leaving for Ephraim. When he realized the young woman had died from her horrific ordeal, he slung her body on one of the donkeys and with his servant, headed for home. Dixon put it this way:

She crawled back to where her lord was.

Being unable to rap on the door;

She fell dead in front of the door

Next morning when her lord arose an’ started upon his journey;

He opened the door an’ find his wife’s lifeless body lying cold in death. (44).

On arriving home “the Levite took a knife, cut up his concubine’s abused body into twelve pieces and sent them throughout Israel”. (45).

Concluding Part 1 of this harrowing tale, Dixon continued:

He divided his wife into twelve parts;

An’ sent one piece to every tribe of Israel.

An’ when they received this human flesh;

They called a special Council.

An’ made a thorough investigation as to why it had been sent to them. (46)

The shocked Israelis demanded the guilty parties to be handed over to them by the Benjamites. But they refused and instead amassed an army outside Gibeah in expectation of an Israeli attack – and they were not to be disappointed!

The shocked Israelis demanded the guilty parties to be handed over to them by the Benjamites. But they refused and instead amassed an army outside Gibeah in expectation of an Israeli attack – and they were not to be disappointed!

There is no mention of how many men raped the concubine [in my copy of the Bible] and one can only suppose that ‘12’ came from the number of gruesome sections of her body the Levite sent out in Israel; to the twelve tribes which would have included the Benjamites, of course. The first reference to twelve men appears in Calvin P. Dixon’s ‘Dry Bones In The Valley – Part 1’ and is replicated by the Jubilee Gospel Team in their version five years later. Before delving into the bloody battles [Judges 20:7] and God’s manipulation of the results [Judges 20:28], it is interesting to note the earlier biblical reference to the Levite’s desperate deed.

“And when he was come into his house, he took a knife, and laid hold on his concubine, and divided her, together with her bones, into twelve pieces, and sent her into all coasts of Israel”. [Judges 19:29]. Add the Israelites’ response and vow of vengeance against the Benjamites: “So all the men of Israel were gathered against the city, knit together as one man”. [Judges 20:11], and we can see where a knowledgeable black preacher could transfer this part of Judges to Ezekiel and the dry bones that knit together and come alive again. This would exonerate Calvin Dixon of an error in his references and elevate him to a truly innovative preacher with a brilliant imagination. Of the 31 obvious [by their related titles] versions listed in Blues & Gospel Records 1890-1943, 14 have been released (as far as I know) on CD. Of these I have – 12! But only Calvin P. Dixon and the Jubilee Gospel Team ‘mix’ the two Books of the Bible’s Old Testament as discussed above.

| Notes | |

| 1. Kamm A. | p.p.117-119 |

| 2. Patterson R.F. | p.292 |

| 3. Kamm | Ibid. p.119 |

| 4. Hill S.G. | p.1271 |

| 5. Boles J.B. | p.1320 |

| 6. Rosenburg B.A. | p.184 |

| 7. Ibid. | |

| 8. Litwack L.F. | p.469 |

| 9. Owen T.M. | p.1187 |

| 10. Smith C. | Notes to DOCD-5414 |

| 11. Evans D. | Notes to Goodbye Babylon (6 x CD set) |

| 12. ‘Straining At A Gnat And Swallowing A Camel’ | Rev. J.M. Gates preaching, vo.; acc. By His Congregation: Deacon Leon Davis speech; prob. either Sister Jordan or Sister Norman speech, vo.; unacc. 18 Mar. 1929. Atlanta, Ga. |

| 13. Litwack | Ibid. |

| 14. ‘Stand By Me’ | Pace Jubilee Singers: Hattie Parker soprano vo.; unk. contralto Vo.; unk. tenor vo.; unk. bass vo.; unk. pno. |

| 15. Heilbut A. | p.25 |

| 16. Haffer C. | p.113 (Lomax interview) |

| 17. Ibid. | |

| 18. Heilbut | Ibid. |

| 19. Ibid. | p.24 |

| 20. Litwack | Ibid. p.471 |

| 21. ‘Revival Day’ | Norfolk Jubilee Quartette: J. ‘Buddie’ Archer ten. Vo.; Otto Tuckson lead vo.; Delrose Hollins bari. vo.; Len Williams bass vo./manager; unacc. c. 1 Jan.. 1926. New York City. |

| 22. Romanowski K. | Notes to DOCD-5531 |

| 23. ‘Revival Day’ | Virginia Female Jubilee Quartet: unk. female quartet vo.; unacc. c. 7 Sept. 1921. N.Y.C. |

| 24 ‘Ha Ha Thisaway’ | Leadbelly vo.gtr., speech. Late May, 1941. N.Y.C. |

| 25.‘Wonderful Counsellor’ | Rev. W.M. Mosley preaching, vo.; acc. His Congregation: mixed group shouts, speech, moaning, vo.; unacc. 7 Dec. 1930. Atlanta, Ga. |

| 26. Ibid. | |

| 27. Evans | Ibid. (CD 6 Tr.12) |

| 28. Ibid. | |

| 29.Ibid. | |

| 30. ‘The Liar’ | Rev. Isaiah Shelton preaching/rapping, vo. speech; unk. female group vo.; unacc. 8 Mar. 1927. New Orleans, La. |

| 31. Genovese E. | p.267 |

| 32. Oliver P. | p.145 |

| 33. Romanowski | Notes to DOCD-5547 |

| 34. Oliver | Ibid. p.140 |

| 35. Lornell C. | p.118 |

| 36. Smith C. | Notes to DOCD-5519 |

| 37. Baldock J. | p.74 |

| 38. Ibid, | (and see Judges 19:1) |

| 39. Waters J. | p.190 |

| 40. Baldock | Ibid. p.76 (and see Judges 19:12) |

| 41. Ibid. | (and see judges 19:22-24) |

| 42. ‘Dry Bones In The Valley’ Part 1 | Calvin P. Dixon ( as ‘Black Billy Sunday’) preaching; unacc. 16 Jan. 1925. N.Y.C. |

| 43. Ibid. | |

| 44. Ibid. | |

| 45. Baldock | Ibid. (and see Judges 19:29; 20:6) |

| 46. Dixon | Ibid. |

| Illustrations | |

| 1. Document Records | Cover of DOCD-5389. Rev. E.D. Campbell. Rev. Isaiah Shelton. Rev. C.F. Thornton’ (Preaching & Congregational Singing) 1927. 1995 |

| 2. McLemore Richard Aubrey (Ed.) | p.? A History Of Mississippi Vol.1 [University College Press Of Mississippi. Jackson] 1973 |

| 3. Oliver Paul | p. 161. Songsters & Saints (Vocal Tradition On Race Records) [Cambridge U. Press] 1984 |

| 4. Document Records | Cover of DOCD-5618. Pace Jubilee Singers Vol.2 1928-1929 + C & MA colored Gospel Quintet (date unk.) 1998 |

| 5. Gabriel Ralph Henry (Ed.) | p.158. The Pageant Of America Vol. III (15 Vols.). Independence Edition. [Yale U. Press. New Haven] 1929 |

| 6. Document Records | Cover of DOCD-5547. Preachers And Congregations Vol.3 1925-1929. 1997 |

| 7. Baldock | p.77. Ibid. |

| Bibliography | |

| Baldock John | Women In The Bible (Miracle Births, Heroic Deeds, Bloodlust And Jealousy) [Capella] 2006 |

| Boles John B. | Great Revival from Encyclopedia Of Southern Culture. Charles Wilson & William Ferris (co-Eds.). [University of North Carolina P. Chapel Hill & London.] 1989 |

| Dixon Robert. M.W. John Godrich. Howard Rye |

Blues & Gospel Records 1890-1943 (4th. Ed.) Revised. [Clarendon Press. Oxford] 1997 |

| Evans David | Notes to CD No.6. from Goodbye Babylon (6 x CDs) [Dust To Digital DTD-01] Oct. 2003 |

| Genovese Eugene | Roll Jordan Roll (The World The Slaves Made) [Pantheon Books.] Rep. 1974. 1st. pub. 1972 |

| Haffer Charles | Lost Delta Found (Rediscovering the Fisk University Library of Congress Coahoma Study, 1941-1942) Quoted in Appendix. John W. Work III. Robert Gordon & Bruce Nemerov (Eds.) Vanderbilt University Press. Nashville] 2005 |

| Heilbut Anthony | The Gospel Sound (Good News & Bad Times) [Limelight Editions. N.Y.] Rev. ed. 1992. 1st. pub. 1971 |

| Hill Samuel | Rituals from Encyclopedia Ibid. |

| Kamm Antony | The Romans – An Introduction [Routledge. London & N.Y] Rep. 1996. 1st. pub. 1995 |

| Litwack Leon F. | Been In The Storm So Long (The Aftermath Of Slavery) [The Athlone Press. London.] 1980 |

| Lornell Christopher | Barrelhouse Singers And Sanctified Preachers from Saints And Sinners, Robert Sacre (Ed.) [Liege University] 1996 |

| Oliver Paul | Songsters & Saints (Vocal Tradition On Race Records) [Cambridge U.Press. Cambridge. London. N.Y. New Rochelle. Melbourne. Sydney] 1984 |

| Owen Thomas McAdory | History Of Alabama And Dictionary Of Alabama Biography (2 Vols.) [The S.J. Clarke Publishing Co. Chicago] 1921 |

| Patterson R.F. | The Cambridge English Dictionary [Tophi Books] 1990 |

| Romanowski Ken | Notes to The Earliest Negro Vocal Groups Vol.4 1921-1924 [Document DOCD-5531] 1997 |

| ———“———– | Notes to Preachers And Congregations Vol.3 1925-1929 [Document DOCD-5547] 1997 |

| Rosenburg Bruce A. | Preacher Black from Encyclopedia Ibid. |

| Smith Chris | Note to The Jubilee Gospel Team 1928 & Deep River Plantation Singers 1931 [Document DOCD-5519] 1997 |

Max Haymes, May 2007

Essay © Copyright 2007 Max Haymes. All rights reserved.

__________________________________________________________________________________________