Here are a small selection of popular early gospel songs, their origins, meanings and legacies.

Ain’t No Grave

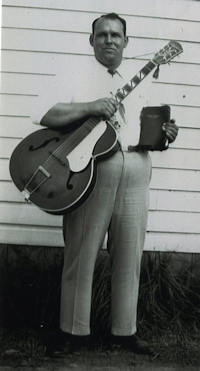

Ain’t No Grave (also known as Gonna Hold This Body Down) is a traditional American gospel song attributed to Claude Ely (1922-1978) of Virginia.

Claude Ely describes composing the song while sick with tuberculosis in 1934 when he was twelve years old. His family prayed for his health, and in response he spontaneously performed this song. Originally recorded by Bozie Sturdivant in 1941 in a slower, African American gospel style and in 1946-7 by Sister Rosetta Tharpe with barrelhouse piano; the song in Ely’s version was recorded in 1953 but composed in 1934. Many notable artists have performed the song, including Johnny Cash on the posthumous album American VI: Ain’t No Grave. The slower, black gospel melody was used by Tharpe into the 1960s, and covered by folksinger Rolf Cahn, and gospel artist Liz McComb. In 1967 the song was featured in the film Cool Hand Luke while Luke (Paul Newman) is digging a grave, performed by Harry Dean Stanton.

The lines “Meet me, Jesus, meet me / Won’t you meet me in the middle of the air / And if my wings should fail me, Lord / Won’t you provide me with another pair” in some recorded versions (including the one by Johnny Cash) are shared with some recorded versions of the traditional song “In My Time of Dying” (including those by Bob Dylan and by Led Zeppelin).

Amazing Grace

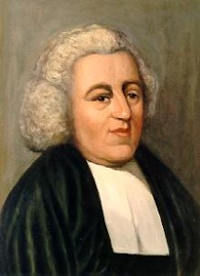

“Amazing Grace” is a Christian hymn published in 1779, with words written in 1772 by the English poet and Anglican clergyman John Newton (1725–1807).

Newton wrote the words from personal experience. He grew up without any particular religious conviction, but his life’s path was formed by a variety of twists and coincidences that were often put into motion by others’ reactions to what they took as his recalcitrant insubordination.

He was pressed (conscripted) into service in the Royal Navy. After leaving the service, he became involved in the Atlantic slave trade. In 1748, a violent storm battered his vessel off the coast of County Donegal, Ireland, so severely that he called out to God for mercy. This moment marked his spiritual conversion but he continued slave trading until 1754 or 1755, when he ended his seafaring altogether. He began studying Christian theology.

Ordained in the Church of England in 1764, Newton became curate of Olney, Buckinghamshire, where he began to write hymns with poet William Cowper. “Amazing Grace” was written to illustrate a sermon on New Year’s Day of 1773. It is unknown if there was any music accompanying the verses; it may have been chanted by the congregation. It debuted in print in 1779 in Newton and Cowper’s Olney Hymns but settled into relative obscurity in England. In the United States, “Amazing Grace” became a popular song used by Baptist and Methodist preachers as part of their evangelizing, especially in the South, during the Second Great Awakening of the early 19th century. It has been associated with more than 20 melodies. In 1835, American composer William Walker set it to the tune known as “New Britain” in a shape-note format. This is the version most frequently sung today.

With the message that forgiveness and redemption are possible regardless of sins committed and that the soul can be delivered from despair through the mercy of God, “Amazing Grace” is one of the most recognisable songs in the English-speaking world. Author Gilbert Chase writes that it is “without a doubt the most famous of all the folk hymns.” Jonathan Aitken, a Newton biographer, estimates that the song is performed about 10 million times annually. It has had particular influence in folk music, and has become an emblematic black spiritual. Its universal message has been a significant factor in its crossover into secular music. “Amazing Grace” became newly popular during a revival of folk music in the US during the 1960s, and it has been recorded thousands of times during and since the 20th century, in versions that have occasionally ranked on popular music charts.

Also check out the book “Amazing Grace” by Steve Turner, published by Lion Books (2005), which traces the life of ‘Amazing Grace’ and the man behind it. The book begins with the dramatic story of John Newton, from his childhood, his life at sea, his participation in the African slave trade through to his writing of ‘Amazing Grace’ and his campaigning against slavery. The second part of the book, picking up the thread in the years immediately following Newton’s death, tells the story of the song itself as it has spread and developed over the past two centuries.

Bye and Bye We’re Going to See the King

“Bye and Bye We’re (or, I’m) Going to See the King” is a Christian song from the African-American musical tradition. It is known by a variety of titles, including “I Wouldn’t Mind Dying (If Dying Was All)” and “A Mother’s Last Word to Her Daughter”. It was recorded seven times before 1930, using the preceding titles. It has been most often recorded in gospel or gospel blues style, but also in other styles such as country.

“Bye and Bye We’re (or, I’m) Going to See the King” is a Christian song from the African-American musical tradition. It is known by a variety of titles, including “I Wouldn’t Mind Dying (If Dying Was All)” and “A Mother’s Last Word to Her Daughter”. It was recorded seven times before 1930, using the preceding titles. It has been most often recorded in gospel or gospel blues style, but also in other styles such as country.

The song consists of several four-line verses (quatrains) and a repeated refrain. The words both of verses and of refrain often differ from one artist to another. A standard feature is that the refrain consists of four lines, the first three of which are identical. Common variants of those three lines include “Bye and bye we’re (or, I’m) going to see the King” and “Holy, holy, holy is His name”. The fourth line almost always begins “(I) wouldn’t (or, don’t) mind dying”. It concludes in various ways in different versions, for example “If dying was all”, or “But I gotta go by myself”, or “Because I’m a child of God”.

“The King” is a title of the Christian God. Many versions include a verse which refers to the vision of the chariot in the Book of Ezekiel, Chapter 1. A line found in many versions, “He said he saw him coming with his dyed garments on”, alludes to the Book of Isaiah at 63:1: Who is this that cometh from Edom, with dyed garments from Bozrah?

“The King” is a title of the Christian God. Many versions include a verse which refers to the vision of the chariot in the Book of Ezekiel, Chapter 1. A line found in many versions, “He said he saw him coming with his dyed garments on”, alludes to the Book of Isaiah at 63:1: Who is this that cometh from Edom, with dyed garments from Bozrah?

Titles like “Bye and Bye We’re Going to See the King” and “I Wouldn’t Mind Dying (If Dying Was All)” are taken from the refrain. The title of the 1929 version by Washington Phillips, “A Mother’s Last Word to Her Daughter”, whose verses differ markedly from other versions, was presumably chosen to indicate that he intended it as a companion song to his “Mother’s Last Word to Her Son” of 1927.

Dark Was the Night, Cold Was the Ground

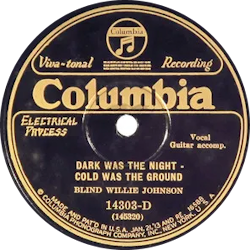

“Dark Was the Night, Cold Was the Ground” is a gospel blues song written and performed by American musician Blind Willie Johnson and recorded in 1927. The song is primarily an instrumental featuring Johnson’s self-taught bottleneck slide guitar and picking style accompanied by his vocalizations of humming and moaning. It has the distinction of being one of 27 samples of music included on the Voyager Golden Record, launched into space in 1977 to represent the diversity of life on Earth. The song has been highly praised and covered by numerous musicians and is featured on the soundtracks of several films.

“Dark Was the Night, Cold Was the Ground” is a gospel blues song written and performed by American musician Blind Willie Johnson and recorded in 1927. The song is primarily an instrumental featuring Johnson’s self-taught bottleneck slide guitar and picking style accompanied by his vocalizations of humming and moaning. It has the distinction of being one of 27 samples of music included on the Voyager Golden Record, launched into space in 1977 to represent the diversity of life on Earth. The song has been highly praised and covered by numerous musicians and is featured on the soundtracks of several films.

Born in 1897, Johnson taught himself how to play guitar and dedicated his life to blues and gospel music, playing for people on street corners and in mission halls. Columbia Records had a field unit that traveled to smaller towns to record local talent. Johnson recorded 30 songs for them at five sessions between 1927 and 1930. Among the first of these was “Dark Was the Night, Cold Was the Ground”.

The song’s title is borrowed from a hymn that was popular in the nineteenth century American South with fasola singers. “Gethsemane”, written by English clergyman Thomas Haweis in 1792, begins with the lines “Dark was the night, cold was the ground / on which my Lord was laid.” Music historian Mark Humphrey describes Johnson’s composition as an impressionistic rendition of “lining out”, a call-and-response style of singing hymns that is common in southern African-American churches.

“Dark Was the Night, Cold Was the Ground” is 3 minutes and 21 seconds of Johnson’s unique guitar playing in open D tuning for slide. By most accounts, Johnson substituted a knife or penknife for the bottleneck. His melancholy, gravel-throated humming of the guitar part creates the impression of “unison moaning”, a melodic style common in Baptist churches where, instead of harmonizing, a choir hums or sings the same vocal part, albeit with slight variations among its members. Although Johnson’s vocals are indiscernible, several sources indicate the subject of the song is the crucifixion of Christ.

“Dark Was the Night, Cold Was the Ground” is 3 minutes and 21 seconds of Johnson’s unique guitar playing in open D tuning for slide. By most accounts, Johnson substituted a knife or penknife for the bottleneck. His melancholy, gravel-throated humming of the guitar part creates the impression of “unison moaning”, a melodic style common in Baptist churches where, instead of harmonizing, a choir hums or sings the same vocal part, albeit with slight variations among its members. Although Johnson’s vocals are indiscernible, several sources indicate the subject of the song is the crucifixion of Christ.

His records were sold by the Columbia and Vocalion labels with other blues acts like Bessie Smith, whom Johnson outsold during the Depression years. In 1928, the influential blues critic Edward Abbe Niles championed Johnson in his column for The Bookman, praising his “violent, tortured, and abysmal shouts and groans, and his inspired guitar playing”.

Johnson’s music experienced a revival in the 1960s thanks in large part to the efforts of blues guitarist Reverend Gary Davis. A highly regarded figure within the burgeoning New York folk scene, Davis gave copies of Johnson’s records to young musicians and taught them to play his songs. The Soul Stirrers, Staples Singers, Buffy Sainte-Marie and Peter, Paul & Mary all covered Johnson. In 1969, the English folk-rock band Fairport Convention released the album What We Did on Our Holidays which included a song inspired by “Dark Was the Night, Cold Was the Ground” called “The Lord Is in this Place…How Dreadful Is this Place”. A compilation album titled Dark Was the Night was released in 2009 by the Red Hot Organization, a charity that raises awareness of HIV and AIDS issues through music. The Kronos Quartet recorded an arrangement of “Dark Was the Night, Cold Was the Ground” that appears on the album. The song “Excavating Rita” by Half Man Half Biscuit on their 2011 album 90 Bisodol (Crimond) quotes the song’s title.

Singer-guitarist Jack White of The White Stripes called “Dark Was the Night, Cold Was the Ground” “the greatest example of slide guitar ever recorded” and used the song as a standard to measure such iconic rock music that followed in its wake, such as “Whole Lotta Love” by Led Zeppelin. In 2003, John Clarke in The Times wrote that “Dark Was the Night, Cold Was the Ground” was “the most intense and startling blues record ever made”. Francis Davis, author of The History of the Blues concurs, writing “In terms of its intensity alone—its spiritual ache—there is nothing else from the period to compare to Johnson’s ‘Dark Was the Night, Cold Was the Ground’, on which his guitar takes the part of a preacher and his wordless voice the part of a rapt congregation.”

Johnson’s recording of “Dark Was the Night, Cold Was the Ground” was selected by the Library of Congress as a 2010 addition to the National Recording Registry, which selects recordings annually that are “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant”.

“Dark was the Night, Cold was the Ground” was used on the Oscar-nominated soundtrack to Pier Paolo Pasolini’s classic film, The Gospel According to St Matthew, in scenes where Judas Iscariot laments betraying Christ and a cripple asks to be healed. Ry Cooder based his soundtrack to the Palme d’Or-winning film, Paris, Texas on “Dark was the Night, Cold was the Ground”, which he has described as “the most soulful, transcendent piece in all American music.” Wim Wenders, the director of Paris, Texas, included Blind Willie Johnson’s music and life in his 2003 documentary The Soul of a Man, produced for the PBS series “The Blues”.

In 1977, Carl Sagan and other researchers collected sounds and images from planet Earth to send on Voyager 1. The Voyager Golden Record includes recordings of frogs, crickets, volcanoes, a human heartbeat, laughter, greetings in 55 languages, and 27 pieces of music. “Dark Was the Night, Cold Was the Ground” was included, according to Timothy Ferris, because “Johnson’s song concerns a situation he faced many times: nightfall with no place to sleep. Since humans appeared on Earth, the shroud of night has yet to fall without touching a man or woman in the same plight.”

Denomination Blues

“Denomination Blues” is a gospel blues song composed by Washington Phillips (1880–1954), and recorded by him (vocals and zither) in 1927. In 1938, Sister Rosetta Tharpe (1915–73) recorded a gospel version of the song under the title “That’s All”. She subsequently recorded several versions with orchestral accompaniment. In 1972, Ry Cooder recorded the song on his album Into the Purple Valley.

“Denomination Blues” is a gospel blues song composed by Washington Phillips (1880–1954), and recorded by him (vocals and zither) in 1927. In 1938, Sister Rosetta Tharpe (1915–73) recorded a gospel version of the song under the title “That’s All”. She subsequently recorded several versions with orchestral accompaniment. In 1972, Ry Cooder recorded the song on his album Into the Purple Valley.

Phillips’ song is in two parts, occupying both sides of a 78rpm single (it is over five minutes long, and could not have fitted on a single side because of technical limitations). In 1928, it sold just over 8,000 copies; a considerable number at a time when a typical single by Bessie Smith, “The Empress of the Blues”, sold around 10,000.

The song is in strophic form: it consists of 17 verses sung to essentially the same music, all with a similar last line. In Part 1, Phillips gently mocks several Christian denominations for their particular obsessions (Primitive Baptists, Missionary Baptists, Amity Methodists, African Methodists, Holiness People, and Church of God); and in Part 2, several types of people he felt were insincere in their beliefs (preachers who want your money, preachers who insist that a college education is needed to preach the gospel, and people who “jump from church to church”). Phillips is known to have attended several churches of different denominations, and the lyrics likely reflect his personal experience. His own faith was uncomplicated, as these extracts from the lyrics show:

I want to tell you, an actual fact,

Every man don’t understand the Bible alike,

But that’s all, I tell you that’s all,

But you’d better have Jesus, I tell you that’s all.

Well, denominations have no right to fight,

They ought to just treat each other right. That’s all.

…

You’re fightin’ each other, and think you’re doing well,

And the sinners on the outside are going to hell. And that’s all.

…

It’s right to stand together, it’s wrong to stand apart,

‘Cause none’s going to heaven but the pure in heart. And that’s all.

The song appears to have been thereafter completely neglected until 1972, when Ry Cooder included a version (with verses omitted and rearranged) on his album Into the Purple Valley. It has since been covered several times. Many cover versions omit some of, or rearrange, or add to, or rewrite, Phillips’ words; perhaps for artistic reasons, or perhaps to support the artist’s own beliefs; sometimes contradicting the message Phillips had tried to convey. Some cover artists, negligently or otherwise, have claimed the song to be their own composition.

In 1938, Sister Rosetta Tharpe recorded a version of the song entitled “That’s All” for Decca Records. She recorded four songs that day, the first gospel songs recorded by Decca; all were immediate successes. The tune is similar to but not identical to Phillips’; the lyrics include some of Phillips’ words (notably the striking phrase “educated fool”, and the words “that’s all” repeated at the end of each verse), but differ in several ways. That, and her choice of title, suggests that she may have learned the song through oral tradition rather than from Phillips’ recording. In 1941, she re-recorded the song, accompanied by Lucky Millinder’s Jazz Orchestra. She continued to perform it throughout her career.

Although Tharpe’s “That’s All” had gained an independent life, the recording history suggests that it and Phillips’ “Denomination Blues” have merged back into a single stream following Cooder’s 1972 cover of the latter song; for example, The 77s’ 1982 version uses both titles.

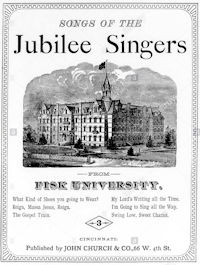

Down by the Riverside

“Down by the Riverside” (also known as “Ain’t Gonna Study War No More” and “Gonna lay down my burden”) is a spiritual. Its roots date back to before the American Civil War, though it was first published in 1918 in Plantation Melodies: A Collection of Modern, Popular and Old-time Negro-Songs of the Southland, Chicago, the Rodeheaver Company. The song has alternatively been known as “Ain’ go’n’ to study war no mo’”, “Ain’t Gwine to Study War No More”, “Down by de Ribberside”, “Going to Pull My War-Clothes” and “Study war no more”. The song was first recorded by the Fisk University jubilee quartet in 1920 (published by Columbia in 1922), and there are at least 14 black gospel recordings before World War II.

“Down by the Riverside” (also known as “Ain’t Gonna Study War No More” and “Gonna lay down my burden”) is a spiritual. Its roots date back to before the American Civil War, though it was first published in 1918 in Plantation Melodies: A Collection of Modern, Popular and Old-time Negro-Songs of the Southland, Chicago, the Rodeheaver Company. The song has alternatively been known as “Ain’ go’n’ to study war no mo’”, “Ain’t Gwine to Study War No More”, “Down by de Ribberside”, “Going to Pull My War-Clothes” and “Study war no more”. The song was first recorded by the Fisk University jubilee quartet in 1920 (published by Columbia in 1922), and there are at least 14 black gospel recordings before World War II.

Because of its pacifistic imagery, “Down by the Riverside” has also been used as an anti-war protest song, especially during the Vietnam War. The song is also included in collections of socialist and labor songs.

The song suggests baptism in water, using the metaphor of crossing the River Jordan to enter the Promised Land in the Old Testament. The refrain of “ain’t gonna study war no more” is a reference to a quotation found in the Old Testament: “nation shall not lift up sword against nation, neither shall they learn war any more.

The Gospel Train

“The Gospel Train (Get on Board)” is a traditional African-American spiritual first published in 1872 as one of the songs of the Fisk Jubilee Singers. A standard Gospel song, it is found in the hymnals of many Protestant denominations and has been recorded by numerous artists.

“The Gospel Train (Get on Board)” is a traditional African-American spiritual first published in 1872 as one of the songs of the Fisk Jubilee Singers. A standard Gospel song, it is found in the hymnals of many Protestant denominations and has been recorded by numerous artists.

The first verse, including the chorus is as follows:

The gospel train is coming

I hear it just at hand

I hear the car wheels moving

And rumbling thro’ the land

Get on board, children (3×)

For there’s room for many a more

Although “The Gospel Train” is usually cited as traditional, several sources credit a Baptist minister from New Hampshire, John Chamberlain, with writing it. Captain Asa W. Bartlett, historian for the New Hampshire Twelfth Regiment, reported Chamberlain as singing the song on April 26, 1863, during Sunday services for the regiment.

The source for the melody and lyrics is unknown but developed out of a tradition which resulted in a number of similar songs about a “Gospel Train”. One of the earliest known is not from the United States, but from Scotland. In 1853, Scotsman John Lyon published a song in Liverpool titled “Be in Time”, the last verse of which mentions that the Gospel train is at hand. Lyon’s book was written to raise funds for the Mormon emigration of the 1840s and 50s. In 1857, an editor for Knickerbocker magazine wrote about visiting a “Colored Camp-Meeting” in New York where a song called “The Warning” was sung which featured an almost identical last verse. “The Warning” used the melody from an old dance song about captain William Kidd.

In 1948, the American born (British by marriage) jazz vocalist Adelaide Hall appeared in a British movie filmed in London called A World is Turning, intended to highlight the contribution of black men and women to British society at a time when they were struggling for visibility on our screens. Filming appears to have been halted due to the director’s illness and only six reels of rushes remain, including scenes of Hall rehearsing songs such as “The Gospel Train” and “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot”.

He’s Got the Whole World in His Hands

“He’s Got the Whole World in His Hands” is a traditional African American spiritual, first published in 1927. It became an international pop hit in 1957–58 in a recording by English singer Laurie London, and has been recorded by many other singers and choirs.

“He’s Got the Whole World in His Hands” is a traditional African American spiritual, first published in 1927. It became an international pop hit in 1957–58 in a recording by English singer Laurie London, and has been recorded by many other singers and choirs.

By many sources, including his published obituary, this song is said to have been written by Master Sergeant Obie Edwin Philpot, although he never held a copyright or earned a royalty.

The song was first published in the paperbound hymnal Spirituals Triumphant, Old and New in 1927. In 1933, it was collected by Frank Warner from the singing of Sue Thomas in North Carolina. It was also recorded by other collectors such as Robert Sonkin of the Library of Congress, who recorded it in Gee’s Bend, Alabama in 1941. That version is still available at the Library’s American Folklife Center.

Frank Warner performed the song during the 1940s and 1950s, and introduced it to the American folk scene. Warner recorded it on the Elektra album American Folk Songs and Ballads in 1952. It was quickly picked up by both American gospel singers and British skiffle and pop musicians.

The song made the popular song charts in a 1957 recording by English singer Laurie London with the Geoff Love Orchestra, which reached #12 on the UK singles chart in late 1957. The songwriting on London’s record was credited to “Robert Lindon” and “William Henry”, which were pseudonyms used by British writers Jack Waller and Ralph Reader, who had used the song in their 1956 stage musical Wild Grows the Heather.

Laurie London’s version then rose to #1 of the Most Played by Jockeys song list in the USA and went to number three on the R&B charts in 1958. The record reached #2 on Billboard’s Best Sellers in Stores survey and #1 in Cashbox’s Top 60. It became a gold record and was the most successful record by a British male in the 1950s in the USA. It was the first, and remains, the only gospel song to hit #1 on a U.S. pop singles chart; “Put Your Hand in the Hand (of the Man)” by Ocean peaked at #2 on the Billboard Hot 100 singles chart in 1971; and “Oh Happy Day” by the Edwin Hawkins Singers reached #3 on the Billboard Hot 100 singles chart in 1969.

Mahalia Jackson’s version made the Billboard top 100 singles chart, topping at number 69. Other versions were recorded by Marian Anderson (in Oslo on August 29, 1958 and released on the single His Master’s Voice 45-6075 AL 6075 and on the extended play En aften på “Casino Non Stop”, introdusert av Arne Hestenes (HMV 7EGN 26. It was arranged by Harry Douglas and Ed Kirkeby), Kate Smith, Odetta, Jackie DeShannon, Perry Como, the Sandpipers (1970; “Come Saturday Morning” LP) and Nina Simone on And Her Friends (recorded 1957). Andy Williams released a version on his 1960 album, The Village of St. Bernadette. In 1982, Raffi recorded the song from his new album Rise and Shine and released it as a single. The Sisters of Mercy played it at the Reading Festival in 1991. It is featured on The Good and the Bad and the Ugly bootleg album. Pat Boone recorded a version for his 1961 album Great, Great, Great. James Booker covered the song on his 1993 album Spiders On The Keys.

I Shall Not Be Moved

“I Shall Not Be Moved” is a Negro spiritual. The song describes how the singer is “like a tree planted by the waters” who “shall not be moved” because of their faith in God. Secularly, as “We Shall Not Be Moved” it gained popularity as a protest and union song of the Civil Rights Movement.

“I Shall Not Be Moved” is a Negro spiritual. The song describes how the singer is “like a tree planted by the waters” who “shall not be moved” because of their faith in God. Secularly, as “We Shall Not Be Moved” it gained popularity as a protest and union song of the Civil Rights Movement.

The text is based on biblical scripture:

Blessed is the man that trusteth in the LORD, and whose hope the LORD is. For he shall be as a tree planted by the waters, and that spreadeth out her roots by the river, and shall not see when heat cometh, but her leaf shall be green; and shall not be careful in the year of drought, neither shall cease from yielding fruit.

— Jeremiah 17:8-9

And he shall be like a tree planted by the rivers of water, that bringeth forth his fruit in his season; his leaf also shall not wither; and whatsoever he doeth shall prosper.

— Psalm 1:3

The song became popular in the Swedish anti-nuclear and peace movements in the late 1970s, in a Swedish translation by Roland von Malmborg, “Aldrig ger vi upp” (‘Never shall we give up’). In Great Britain in the 1980s the song was used by the popular British wrestler Big Daddy as his walk-on music, which would be greeted by cheers from the fans.

David Spener has written a book documenting the history of this song title, including how it was translated into Spanish, changing the first singular to first person plural, “No Nos Moverán”

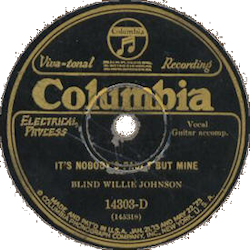

It’s Nobody’s Fault but Mine

“It’s Nobody’s Fault but Mine” or “Nobody’s Fault but Mine” is a song first recorded by gospel blues artist Blind Willie Johnson in 1927. It is a solo performance with Johnson singing and playing slide guitar. The song has been interpreted and recorded by numerous musicians in a variety of styles, including Led Zeppelin in 1975.

“It’s Nobody’s Fault but Mine” or “Nobody’s Fault but Mine” is a song first recorded by gospel blues artist Blind Willie Johnson in 1927. It is a solo performance with Johnson singing and playing slide guitar. The song has been interpreted and recorded by numerous musicians in a variety of styles, including Led Zeppelin in 1975.

“It’s Nobody’s Fault but Mine” tells of a spiritual struggle, with reading the Bible as the path to salvation, or, rather, the failure to read it leading to damnation. Johnson was blinded at age seven when his stepmother threw a caustic solution and his verses attribute his father, mother, and sister with teaching him how to read. The context of this song is strictly religious. Johnson’s song is a melancholy expression of his spirit, as the blues style echoes the depths of his guilt and his struggle. An early review called the song “violent, tortured and abysmal shouts and groans and his inspired guitar playing in a primitive and frightening Negro religious song”.

In performing the song, Johnson alternated between vocal and solo slide-guitar melody lines on the first and second or sometimes third and fourth strings. Eric Clapton commented: “That’s probably the finest slide guitar playing you’ll ever hear. And to think that he did it with a penknife, as well.” Johnson’s guitar is tuned to an open D chord with a capo on the first fret and he provides an alternating bass figure with his thumb.

“It’s Nobody’s Fault but Mine” was one of the first songs recorded by Johnson for Columbia Records. The session took place in Dallas, Texas, on December 3, 1927. Columbia released it as his second single on the then-standard 78 rpm record format, with “Dark Was the Night, Cold Was the Ground” as the second side. In the 1930s, the single was also issued by Vocalion Records and other labels. In 1957, the song was included on the Folkways Records’ compilation album Blind Willie Johnson – His Story, with narration by Samuel Charters. Over the years, it has been included on numerous Johnson and blues compilations, including The Complete Blind Willie Johnson (1993), the comprehensive CD set of his recordings for Columbia.

“It’s Nobody’s Fault but Mine” was one of the first songs recorded by Johnson for Columbia Records. The session took place in Dallas, Texas, on December 3, 1927. Columbia released it as his second single on the then-standard 78 rpm record format, with “Dark Was the Night, Cold Was the Ground” as the second side. In the 1930s, the single was also issued by Vocalion Records and other labels. In 1957, the song was included on the Folkways Records’ compilation album Blind Willie Johnson – His Story, with narration by Samuel Charters. Over the years, it has been included on numerous Johnson and blues compilations, including The Complete Blind Willie Johnson (1993), the comprehensive CD set of his recordings for Columbia.

“It’s Nobody’s Fault but Mine” is one of Johnson’s most interpreted songs. Many artists have recorded it as “Nobody’s Fault but Mine” as well as the original title, with the songwriting credits including Blind Willie Johnson, public domain, and traditional.

Lyrically, “Nobody’s Fault but Mine” has been compared to Robert Johnson’s “Hell Hound on My Trail”. Johnson’s 1937 Delta blues song tells of a man trying to stay ahead of the evil which is pursuing him, but it does not address the cause or lasting solution for his predicament. In Blind Willie Johnson’s “It’s Nobody’s Fault but Mine”, the problem is clearly stated: he will be doomed, unless he uses his abilities to learn (and presumably live according to) biblical teachings.

John the Revelator

“John the Revelator” is a traditional gospel blues call and response song. Music critic Thomas Ward describes it as “one of the most powerful songs in all of pre-war acoustic music … [which] has been hugely influential to blues performers”. American gospel-blues musician Blind Willie Johnson recorded “John the Revelator” in 1930 and subsequently a variety of artists have recorded their renditions of the song, often with variations in the verses and music.

“John the Revelator” is a traditional gospel blues call and response song. Music critic Thomas Ward describes it as “one of the most powerful songs in all of pre-war acoustic music … [which] has been hugely influential to blues performers”. American gospel-blues musician Blind Willie Johnson recorded “John the Revelator” in 1930 and subsequently a variety of artists have recorded their renditions of the song, often with variations in the verses and music.

The song’s title refers to John of Patmos in his role as the author of the Book of Revelation. A portion of that book focuses on the opening of seven seals and the resulting apocalyptic events. In its various versions, the song quotes several passages from the Bible in the tradition of American spirituals.

Blind Willie Johnson recorded “John the Revelator” during his fifth and final recording session for Columbia Records in Atlanta, Georgia on April 20, 1930. Accompanying Johnson on vocal and guitar is Willie B. Harris (sometimes identified as his first wife), who sings the response parts of the song. Their vocals add a “sense of dread and foreboding” to the song, along with the chorus line “Who’s that a writin’, John the Revelator” “repeated like a mantra”. The song was released as one of the last singles by Johnson and is included on numerous compilations, including the 1952 Anthology of American Folk Music.

Delta blues musician Son House recorded several a cappella versions of “John the Revelator” in the 1960s. His lyrics for a 1965 recording explicitly reference three theologically important events: the Fall of Man, the Passion of Christ, and the Resurrection. This version was included on the 1965 album The Legendary Son House: Father of the Folk Blues (Columbia). An alternate version from the same session is found on the 1992 reissue Son House — Father of the Delta Blues: The Complete 1965 Sessions (Columbia).

Mary Don’t You Weep

“Mary Don’t You Weep” (alternately titled “O Mary Don’t You Weep”, “Oh Mary, Don’t You Weep, Don’t You Mourn”, or variations thereof) is a Spiritual that originates from before the American Civil War – thus it is what scholars call a “slave song,” “a label that describes their origins among the enslaved,” and it contains “coded messages of hope and resistance.” It is one of the most important of Negro spirituals.

“Mary Don’t You Weep” (alternately titled “O Mary Don’t You Weep”, “Oh Mary, Don’t You Weep, Don’t You Mourn”, or variations thereof) is a Spiritual that originates from before the American Civil War – thus it is what scholars call a “slave song,” “a label that describes their origins among the enslaved,” and it contains “coded messages of hope and resistance.” It is one of the most important of Negro spirituals.

The song tells the Biblical story of Mary of Bethany and her distraught pleas to Jesus to raise her brother Lazarus from the dead. Other narratives relate to The Exodus and the Passage of the Red Sea, with the chorus proclaiming Pharaoh’s army got drown-ded! and to God’s rainbow covenant to Noah after the Great Flood. With liberation thus one of its themes, the song again becomes popular during the Civil Rights Movement. Additionally, a song that explicitly chronicles the victories of the Civil Rights Movement, “If You Miss Me from the Back of the Bus”, written by Charles Neblett of The Freedom Singers, was sung to this tune and became one of the most well-known songs of that movement.

The first recording of the song was by the Fisk Jubilee Singers in 1915. The best known recordings were made by the vocal gospel group The Caravans in 1958, with Inez Andrews as the lead singer, and The Swan Silvertones in 1959. “Mary Don’t You Weep” became The Swan Silvertones’ greatest hit, and lead singer Claude Jeter’s interpolation “I’ll be a bridge over deep water if you trust in my name” served as Paul Simon’s inspiration to write his 1970 song “Bridge over Troubled Water”. The spiritual’s lyric God gave Noah the rainbow sign, no more water the fire next time inspired the title for The Fire Next Time, James Baldwin’s 1963 account of race relations in America.

In 2015 it was announced that The Swan Silvertones’s version of the song will be inducted into the Library of Congress’s National Recording Registry for the song’s “cultural, artistic and/or historical significance to American society and the nation’s audio legacy”.

In 2015 it was announced that The Swan Silvertones’s version of the song will be inducted into the Library of Congress’s National Recording Registry for the song’s “cultural, artistic and/or historical significance to American society and the nation’s audio legacy”.

Many other recordings have been made, by artists ranging from The Soul Stirrers to Burl Ives. Bing Crosby included the song in a medley on his album 101 Gang Songs (1961). Pete Seeger gave it additional folk music visibility by performing it at the 1964 Newport Folk Festival, and played it many times throughout his career, adapting the lyrics and stating the song’s relevance as an American song, not just a spiritual. In 1960, Stonewall Jackson recorded a country version of the song, where Mary is a young woman left by her lover on the wedding day to fight in the civil war, and he died in the burning of Atlanta; the song became a hit when it peaked at #12 in Country charts and #41 in Pop charts. In the 1960s, Jamaican artist Justin Hinds had a ska hit with “Jump Out Of The Frying Pan”, whose lyrics borrowed heavily from the spiritual. Paul Clayton’s version “Pharaoh’s Army” appears in “Home-Made Songs & Ballads”, which was released in 1961. James Brown rewrote the lyrics of the original spiritual for his 1964 soul hit with his vocal group The Famous Flames, “Oh Baby Don’t You Weep”. Aretha Franklin recorded a live version of the song for her 1972 album Amazing Grace. An a cappella version by Take 6, simply called “Mary”, received wide airplay after appearing on the group’s eponymous debut album in 1988. The song is sung briefly at the beginning of the music video for Bone Thugs N Harmony’s 1996 “Tha Crossroads”. In a pounding big group folk arrangement, it was one of the highlights of the 2006 Bruce Springsteen with The Seeger Sessions Band Tour. The song also appeared on Mike Farris’ 2007 album Salvation in Lights. This song appears in the Peter Yarrow Songbook and on the accompanying recorded album, “Favorite Folks Songs.” Entitled as “Don’t You Weep, Mary”, this song is on The Kingston Trio album Close-Up.

Move On Up A Little Higher

“Move On Up A Little Higher” is a gospel song written by W. Herbert Brewster, first recorded by Brother John Sellers in late 1946, but most famously recorded on September 12, 1947, by gospel singer Mahalia Jackson, a version that sold eight million copies. The song was honored with the Grammy Hall of Fame Award in (1998). In 2005, the Library of Congress honored the song by adding it to the National Recording Registry. It was also included in the list of Songs of the Century, by the Recording Industry of America and the National Endowment for the Arts, and is in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame as one of the 500 songs that shaped rock.

“Move On Up A Little Higher” is a gospel song written by W. Herbert Brewster, first recorded by Brother John Sellers in late 1946, but most famously recorded on September 12, 1947, by gospel singer Mahalia Jackson, a version that sold eight million copies. The song was honored with the Grammy Hall of Fame Award in (1998). In 2005, the Library of Congress honored the song by adding it to the National Recording Registry. It was also included in the list of Songs of the Century, by the Recording Industry of America and the National Endowment for the Arts, and is in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame as one of the 500 songs that shaped rock.

Composer Rev. William Herbert Brewster (1897-1987) composed “Moved On Up A Little Higher,” through the imagery of a “Christian climbing the ladder to heaven,” the song encourages black upward mobility, hence reflecting the postwar Afro-modernist sentiments:”

“The fight for rights here in Memphis was pretty rough on the Black church . . . and I wrote that song “Move Up a Little Higher”… We’ll have to move in the field of education. Move into the professions and move into politics. Move in anything that any other race has to have to survive. That was a protest idea and inspiration. I was trying to inspire Black people to move up higher. Don’t be satisfied with the mediocre…Before the freedom fights started, before the Martin Luther King days, I had to lead a lot of protest meetings. In order to get my message over, there were things that were almost dangerous to say, but you could sing it.”

“Move on Up” was originally written for one of Brewster’s religious pageants or passion plays. Brewster’s maintained that the entire piece—lyrics, melody, and harmony—came to him in one flow, and shortly thereafter he taught the song to his principle vocal soloist, Queen C. Anderson. But it was the Queen of Gospel, Mahalia Jackson, who, according to Brewster, “knew what to do with it. She could throw the verse out there.” Producer Art Freeman insisted Jackson record “Move on Up a Little Higher”; released in December 1947, the single became the best-selling gospel record of all time, selling in such great quantities that stores could not even meet the demand. Brewster was pastor of East Trigg Avenue Baptist Church, one of the churches where young Elvis Presley studied the ecstatic moves of his gospel heroes.

Old-Time Religion

(“Give Me That”) “Old-Time Religion” (and similar spellings) is a traditional Gospel song dating from 1873, when it was included in a list of Jubilee songs – or earlier. It has become a standard in many Protestant hymnals, though it says nothing about Jesus or the gospel, and covered by many artists. Some scholars, such as Forrest Mason McCann, have asserted the possibility of an earlier stage of evolution of the song, in that “the tune may go back to English folk origins” (later dying out in the white repertoire but staying alive in the work songs of African Americans). In any event, it was by way of Charles Davis Tillman that the song had incalculable influence on the confluence of black spiritual and white gospel song traditions in forming the genre now known as southern gospel. Tillman was largely responsible for publishing the song into the repertoire of white audiences. It was first heard sung by African-Americans and written down by Tillman when he attended a camp meeting in Lexington, South Carolina in 1889.

(“Give Me That”) “Old-Time Religion” (and similar spellings) is a traditional Gospel song dating from 1873, when it was included in a list of Jubilee songs – or earlier. It has become a standard in many Protestant hymnals, though it says nothing about Jesus or the gospel, and covered by many artists. Some scholars, such as Forrest Mason McCann, have asserted the possibility of an earlier stage of evolution of the song, in that “the tune may go back to English folk origins” (later dying out in the white repertoire but staying alive in the work songs of African Americans). In any event, it was by way of Charles Davis Tillman that the song had incalculable influence on the confluence of black spiritual and white gospel song traditions in forming the genre now known as southern gospel. Tillman was largely responsible for publishing the song into the repertoire of white audiences. It was first heard sung by African-Americans and written down by Tillman when he attended a camp meeting in Lexington, South Carolina in 1889.

Peace in the Valley

“Peace in the Valley” is a 1937 song written by Thomas A. Dorsey, originally for Mahalia Jackson. The song became a hit in 1951 for Red Foley and the Sunshine Boys, reaching number seven on the Country & Western Best Seller chart. It was among the first gospel recordings to sell one million copies. Foley’s version was a 2006 entry into the Library of Congress’ National Recording Registry.

In 1950, it was one of the first songs recorded by a young Sam Cooke, during his tenure as lead singer of the Soul Stirrers.

After the success of Red Foley’s interpretation, Jo Stafford recorded the song for her 1954 gospel album Garden of Prayer.

The song achieved enormous celebrity during Elvis Presley’s third and final appearance on the Ed Sullivan Show on January 6 of 1957. Before an audience estimated at 52.4 million viewers, Presley closed the show by dedicating the song to the 250,000 refugees fleeing Hungary after the 24 and 31 October 1956 double-invasion of that country by the Soviet Union. Because he also requested that immediate aid be sent to lessen their plight, the appeal in turn yielded contributions amounting to US$6 million, or the equivalent of US$49.5 million in today’s dollars. Over the next 11 months, the International Red Cross in Geneva, with the help of the US Air Force, organized the distribution of both perishables and non-perishables purchased with the above-mentioned funds (Swiss Francs 26.2 million, at the then 4.31 CHFR-US$ exchange) to the refugees in both Austria and England where they settled for life. On October 15, 1957, Presley’s first Christmas album, containing a master studio recording of the song, was released, topping the Billboard Charts for 4 weeks and selling in excess of three million copies, as certified by the RIAA on 15 July of 1999. Because of these extraordinary developments, István Tarlós, the Mayor of the city of Budapest, in 2011 and as a gesture of belated gratitude, named a park after him, as well as making him an honorary citizen.

Eventually, the song became a country-pop favorite and was recorded by Little Richard on his 1961 Quincy Jones-produced gospel album The King of the Gospel Singers; Connie Francis on her 1961 album Sing Along with Connie Francis; George Jones on his 1962 album Homecoming in Heaven; Johnny Cash on his 1969 At San Quentin live album (he recorded the studio version in 1962 and released it as a single) ; Loretta Lynn; Dolly Parton; Screaming Trees, as a B-side to their “Dollar Bill” single; Ronnie Milsap; Art Greenhaw with the Jordanaires, Tom Brumley and the Light Crust Doughboys for the Grammy-Nominated album starring Ann-Margret titled God Is Love: The Gospel Sessions, and Faith Hill, for a concert special.

Steal Away

“Steal Away” (“Steal Away to Jesus”) is an American Negro spiritual. The song is well known by variations of the chorus:

“Steal Away” (“Steal Away to Jesus”) is an American Negro spiritual. The song is well known by variations of the chorus:

Steal away, steal away, steal away to Jesus!

Steal away, steal away home, I hain’t got long to stay here

Songs such as “Steal Away to Jesus”, “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot”, “Wade in the Water” and the “Gospel Train” are songs with hidden codes, not only about having faith in God, but containing hidden messages for slaves to run away on their own, or with the Underground Railroad.

“Steal Away” the song was composed by Wallace Willis, a slave of a Choctaw freedman in the old Indian Territory, sometime before 1862. Alexander Reid, a minister at a Choctaw boarding school, heard Willis singing the songs and transcribed the words and melodies. He sent the music to the Jubilee Singers of Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee. The Jubilee Singers then popularized the songs during a tour of the United States and Europe.

“Steal Away” the song is a standard Gospel song, and is found in the hymnals of many Protestant denominations. An arrangement of the song is included in the oratorio A Child of Our Time, first performed in 1944, by the classical composer Michael Tippett (1908–98). Many recordings of the song have been made including versions by Pat Boone and Nat King Cole.

Swing Low, Sweet Chariot

“Swing Low, Sweet Chariot” is an American Negro spiritual. The earliest known recording was in 1909, by the Fisk Jubilee Singers of Fisk University.

“Swing Low, Sweet Chariot” is an American Negro spiritual. The earliest known recording was in 1909, by the Fisk Jubilee Singers of Fisk University.

In 2002, the Library of Congress honored the song as one of 50 recordings chosen that year to be added to the National Recording Registry. It was also included in the list of Songs of the Century, by the Recording Industry Association of America and the National Endowment for the Arts.

“Swing Low, Sweet Chariot” was written by Wallis Willis, a Choctaw freedman in the old Indian Territory in what is now Choctaw County, near the County seat of Hugo, Oklahoma sometime after 1865. He may have been inspired by the sight of the Red River, by which he was toiling, which reminded him of the Jordan River and of the Prophet Elijah’s being taken to heaven by a chariot (2 Kings 2:11). Some sources claim that this song and “Steal Away” (also sung by Willis) had lyrics that referred to the Underground Railroad, the freedom movement that helped black people escape from Southern slavery to the North and Canada.

Alexander Reid, a minister at the Old Spencer Academy, a Choctaw boarding school, heard Willis singing these two songs and transcribed the words and melodies. He sent the music to the Jubilee Singers of Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee. The Jubilee Singers popularized the songs during a tour of the United States and Europe.

In 1939, Nazi Germany’s Reich Music Examination Office added the song to a listing of “undesired and harmful” musical works.

The song enjoyed a resurgence during the 1960s Civil Rights struggle and the folk revival; it was performed by a number of artists. Perhaps the most famous performance during this period was that by Joan Baez during the legendary 1969 Woodstock festival.

Oklahoma State Senator Judy Eason McIntyre from Tulsa proposed a bill nominating “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot” as the Oklahoma State official gospel song in 2011. The bill was co-sponsored by the Oklahoma State Black Congressional Caucus. Oklahoma Governor Mary Fallin signed the bill into law on May 5, 2011, at a ceremony at the Oklahoma Cowboy Hall of Fame; making the song the official Oklahoma State Gospel Song.

A popular early recording was by the Fisk University Jubilee Quartet for Victor Records (No. 16453) on December 1, 1909 and two years later the Apollo Jubilee Quartette recorded the song on Monday, February 26, 1912, Columbia Records (A1169), New York City.

Since then, numerous versions have been recorded including those by Bing Crosby (recorded April 25, 1938), Kenny Ball and His Jazzmen (included in the album The Kenny Ball Show – 1962), Louis Armstrong (for his album Louis and the Good Book – 1958), Sam Cooke (for his album Swing Low – 1961), Vince Hill (1993), Peggy Lee (1946), and Paul Robeson (recorded January 7, 1926 for Victor – (No. 20068).

British rock musician Eric Clapton recorded a reggae version of the song for his 1975 studio album There’s One in Every Crowd. RSO Records released it with the B-side “Pretty Blue Eyes” as a seven-inch gramophone single in May the same year, produced by Tom Dowd. His version reached various singles charts, including Japan, the Netherlands, New Zealand and the United Kingdom.

“Swing Low, Sweet Chariot” has been sung by rugby players and fans for some decades. It became associated with the English national side. The song is still regularly sung at matches by English supporters.

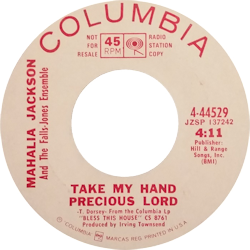

Take My Hand, Precious Lord

“Take My Hand, Precious Lord” (a.k.a. “Precious Lord, Take My Hand”) is a gospel song. The lyrics were written by the Rev. Thomas A. Dorsey, who also adapted the melody.

The melody is credited to Dorsey, drawn extensively from the 1844 hymn tune, “Maitland”. “Maitland” is often attributed to American composer George N. Allen (1812–1877), but the earliest known source (Plymouth Collection, 1855) shows that Allen was the author/adapter of the text “Must Jesus bear the cross alone,” not the composer of the tune, and the tune itself was printed without attribution for many years. “Maitland” is also sometimes attributed to The Oberlin Social and Sabbath School Hymn Book, which Allen edited, but this collection does not contain music. This tune originally appeared in hymnals and tune books as “Cross and Crown”; the name “Maitland” appears as early as 1868. Dorsey said that he had heard Blind Connie Williams sing his version of this song with “Precious Lord” and used it as inspiration. Dorsey wrote “Precious Lord” in response to his inconsolable bereavement at the death of his wife, Nettie Harper, in childbirth, and his infant son in August 1932. (Mr. Dorsey can be seen telling this story in the 1981 gospel music documentary Say Amen, Somebody.) The earliest known recording was made on February 16, 1937, by the Heavenly Gospel Singers (Bluebird B6846). “Take My Hand, Precious Lord” is published in more than 40 languages.

It was Martin Luther King Jr.’s favorite song, and he often invited gospel singer Mahalia Jackson to sing it at civil rights rallies to inspire crowds; at his request she sang it at his funeral in April 1968. King’s last words before his assassination was a request to play it at a mass he was due to attend that night. Opera singer Leontyne Price sang it at the state funeral of President Lyndon B. Johnson in January 1973, and Aretha Franklin sang it at Mahalia Jackson’s funeral in 1972. Franklin also recorded a live version of the song for her album Amazing Grace (1972) as a medley with “You’ve Got a Friend”. It was sung by Nina Simone at the Westbury Music Fair on April 7, 1968, three days after King’s assassination. That evening was dedicated to him and recorded on the album ‘Nuff Said!. It was also performed by Ledisi in the movie and soundtrack for Selma in which Ledisi portrays Mahalia Jackson. It was also performed by Beyoncé at the 57th Annual Grammy Awards on February 8, 2015. Dave Grohl recited the lyrics of the song at a remembrance service for his friend, Lemmy from Motörhead, in January 2016.

It was Martin Luther King Jr.’s favorite song, and he often invited gospel singer Mahalia Jackson to sing it at civil rights rallies to inspire crowds; at his request she sang it at his funeral in April 1968. King’s last words before his assassination was a request to play it at a mass he was due to attend that night. Opera singer Leontyne Price sang it at the state funeral of President Lyndon B. Johnson in January 1973, and Aretha Franklin sang it at Mahalia Jackson’s funeral in 1972. Franklin also recorded a live version of the song for her album Amazing Grace (1972) as a medley with “You’ve Got a Friend”. It was sung by Nina Simone at the Westbury Music Fair on April 7, 1968, three days after King’s assassination. That evening was dedicated to him and recorded on the album ‘Nuff Said!. It was also performed by Ledisi in the movie and soundtrack for Selma in which Ledisi portrays Mahalia Jackson. It was also performed by Beyoncé at the 57th Annual Grammy Awards on February 8, 2015. Dave Grohl recited the lyrics of the song at a remembrance service for his friend, Lemmy from Motörhead, in January 2016.

This Little Light of Mine

“This Little Light of Mine” is a gospel song written for children in the 1920s by Harry Dixon Loes. It was later adapted by Zilphia Horton, amongst many other activists, in connection with the civil rights movement. Although the words of the song have a Biblical theme, it is unclear as to which specific Bible verse it is based upon. Today, many versions of the song are available.

Harry Dixon Loes, who studied at the Moody Bible Institute and the American Conservatory of Music, was a musical composer and teacher, who wrote or co-wrote several other gospel songs. The song has since entered the folk tradition, first being collected by John Lomax in 1939. Often thought of as a Negro spiritual, it can be found in The United Methodist Hymnal, #585, adapted by William Farley Smith in 1987.

The song takes its theme from some of Jesus’s remarks to his followers. Matthew 5:14-16 of the King James Version gives: “Ye are the light of the world. A city that is set on an hill cannot be hid. Neither do men light a candle and put it under a bushel, but on a candlestick; and it giveth light unto all that are in the house. Let your light shine before men, that they may see your good works and give glory to your Father who is in the heaven.” The parallel passage in Luke 11:33 of the King James Version gives: “No man, when he hath lighted a candle, putteth it in a secret place, neither under a bushel, but on a candlestick, that they which come in may see the light.”

The song has also been secularised into “This Little Girl of Mine” as recorded by Ray Charles in 1956 and later The Everly Brothers. It has often been published with a set of hand movements to be used for the instruction of children.

Under the influence of Zilphia Horton, Fannie Lou Hamer, and others, it eventually became a Civil Rights anthem in the 1950s and 1960s, especially the version by Bettie Mae Fikes. The Seekers recorded it for their second UK album, Hide & Seekers (also known as The Four & Only Seekers) in 1964. Over time it also became a very popular children’s song, recorded and performed by the likes of Raffi in the 1980s from his album Rise and Shine, releasing it as a single. It is sometimes included in Christian children’s song books.

Odetta and the Boys Choir of Harlem performed the song on the Late Show with David Letterman on September 17, 2001, on the first show after Letterman resumed broadcasting, after having been off the air for several nights following the events of 9/11.

LZ7 took their version of the song named “This Little Light” to number 26 in the UK Singles Chart.

The song is sung in several scenes of the 1994 film Corrina, Corrina starring Whoopi Goldberg and Ray Liotta.

This Train

“This Train”, also known as “This Train Is Bound for Glory”, is a traditional American gospel song first recorded in 1922. Although its origins are unknown, the song was relatively popular during the 1920s as a religious tune, and it became a gospel hit in the late 1930s for singer-guitarist Sister Rosetta Tharpe. After switching from acoustic to electric guitar, Tharpe released a more secular version of the song in the early 1950s.

“This Train”, also known as “This Train Is Bound for Glory”, is a traditional American gospel song first recorded in 1922. Although its origins are unknown, the song was relatively popular during the 1920s as a religious tune, and it became a gospel hit in the late 1930s for singer-guitarist Sister Rosetta Tharpe. After switching from acoustic to electric guitar, Tharpe released a more secular version of the song in the early 1950s.

The song’s popularity was also due in part to the influence of folklorists John A. Lomax and Alan Lomax, who discovered the song while making field recordings in the American South in the early 1930s and included it in folk song anthologies that were published in 1934 and 1960. These anthologies brought the song to the attention of an even broader audience during the folk music revival of the 1950s and 1960s.

The earliest known example of “This Train” is a recording by Florida Normal and Industrial Institute Quartette from 1922, under the title “Dis Train”. Another one of the earliest recordings of the song is the version made by Wood’s Blind Jubilee Singers in August 1925 under the title “This Train Is Bound for Glory”. Between 1926 and 1931, three other black religious groups recorded it. During a visit to the Parchman Farm state penitentiary in Mississippi in 1933, Smithsonian Institution musicologist John A. Lomax and his son Alan made a field recording of the song by black inmate Walter McDonald. The next year the song found its way into print for the first time in the Lomaxes’ American Folk Songs and Ballads anthology and was subsequently included in Alan Lomax’s 1960 anthology Folk Songs of North America.

In 1935, the first hillbilly recording of the song was released by Tennessee Ramblers as “Dis Train” in reference to the song’s black roots. Then in the late 1930s, after becoming the first black artist to sign with a major label, gospel singer and guitarist Sister Rosetta Tharpe recorded “This Train” as a hit for Decca. Her later version of the song, released by Decca in the early 1950s, featured Tharpe on electric guitar and is cited as one of several examples of her work that led to the emergence of rock ‘n roll.

In 1955, the song, with altered lyrics, became a popular single for blues singer-harmonica player Little Walter Jacobs as “My Babe”. This secular adaptation has since become a rock standard recorded by many artists, including Dale Hawkins, Bo Diddley, Cliff Richard (three times), and The Remains.

Over the years, “This Train” has been covered by artists specializing in numerous genres, including blues, folk, bluegrass, gospel, rock, post-punk, jazz, reggae, and zydeco.

The song provided the inspiration for the title of Woody Guthrie’s autobiographical novel Bound for Glory. The book was subsequently used as the basis for director Hal Ashby’s 1976 film Bound for Glory on Guthrie’s life, which starred David Carradine in the lead role.

Sister Rosetta Tharpe’s 1950s version of “This Train” was featured as a selection on Bob Dylan’s XM Satellite Radio program Theme Time Radio Hour, during its first season in 2006–2007. The song, which was played on Show 46, “More Trains”, was later released on The Best of Bob Dylan’s Theme Time Radio Hour, Volume 1 on the Chrome Dreams label.

When the Saints Go Marching In

“When the Saints Go Marching In,” often referred to as “The Saints,” is a black spiritual. Though it originated as a Christian hymn, it is often played by jazz bands. This song was famously recorded on May 13, 1938, by Louis Armstrong and his orchestra. The song is sometimes confused with a similarly titled composition “When the Saints Are Marching In” from 1896 by Katharine Purvis (lyrics) and James Milton Black (music).

“When the Saints Go Marching In,” often referred to as “The Saints,” is a black spiritual. Though it originated as a Christian hymn, it is often played by jazz bands. This song was famously recorded on May 13, 1938, by Louis Armstrong and his orchestra. The song is sometimes confused with a similarly titled composition “When the Saints Are Marching In” from 1896 by Katharine Purvis (lyrics) and James Milton Black (music).

The origins of this song are unclear. It apparently evolved in the early 1900s from a number of similarly titled gospel songs, including “When the Saints Are Marching In” (1896) and “When the Saints March In for Crowning” (1908). The first known recorded version was in 1923 by the Paramount Jubilee Singers on Paramount 12073. Although the title given on the label is “When All the Saints Come Marching In”, the group sings the modern lyrics beginning with “When the saints go marching in”. No author is shown on the label. Several other gospel versions were recorded in the 1920s, with slightly varying titles but using the same lyrics, including versions by The Four Harmony Kings (1924), Elkins-Payne Jubilee Singers (1924), Wheat Street Female Quartet (1925), Bo Weavil Jackson (1926), Deaconess Alexander (1926), Rev. E. D. Campbell (1927), Robert Hicks (AKA Barbecue Bob, 1927), Blind Willie Davis (1928), and the Pace Jubilee Singers (1928).

The earliest versions were slow and stately, but as time passed, the recordings became more rhythmic, including a distinctly uptempo version by the Sanctified Singers on British Parlophone in 1931.

Even though the song had folk roots, a number of composers claimed copyright in it in later years, including Luther G. Presley and Virgil Oliver Stamps, R. E. Winsett. The tune is particularly associated with the city of New Orleans. A jazz standard, it has been recorded by many jazz and pop artists.

As with many numbers with long traditional folk use, there is no one “official” version of the song or its lyrics. This extends so far as confusion as to its name, with it often being mistakenly called “When the Saints Come Marching In.” As for the lyrics themselves, their very simplicity makes it easy to generate new verses. Since the first and second lines of a verse are exactly the same, and the third and fourth are standard throughout, the creation of one suitable line in iambic tetrameter generates an entire verse.

The song is apocalyptic, taking much of its imagery from the Book of Revelation, but excluding its more horrific depictions of the Last Judgment. The verses about the Sun and Moon refer to Solar and Lunar eclipses; the trumpet (of the Archangel Gabriel) is the way in which the Last Judgment is announced. As the hymn expresses the wish to go to Heaven, picturing the saints going in (through the Pearly Gates), it is entirely appropriate for funerals.

_____________________________________________________________________

All Sources: Wikipedia

_____________________________________________________________________