Synopsis

Gospel blues is a blues-based form of gospel music (a combination of blues guitar and evangelistic lyrics). Notable gospel blues performers include Thomas A. Dorsey (the “founder” of gospel blues), Blind Willie Johnson, Sister Rosetta Tharpe and Reverend Gary Davis. Blues musicians such as Blind Lemon Jefferson, Charley Patton, Sam Collins, Josh White, Blind Boy Fuller, Blind Willie McTell, Bukka White, Sleepy John Estes and Skip James have recorded a fair number of Gospel and religious songs, these were often commercially released under a pseudonym. Additionally, by the late 1950s and 1960s some musicians had become devote, or even practicing clergymen, this was the case for musicians such as Reverend Robert Wilkins and Ishman Bracey.

__________________________________________________________________

Explanatory Articles

“Among those whose ears perked up in August 1926 when OKeh released the first two 78s by “the Blind Race Evangelist” (Arizona Dranes) was Thomas A. Dorsey, who would go on to be called “the Father of Gospel”. In a 1961 interview, Dorsey gave Dranes some credit with opening his mind to laying secular styles under religious themes. Although he was a Baptist, Dorsey liked to step inside the heat of sanctified services for inspiration, as did his protégé Mahalia Jackson. “If I can put some of what she does and mix it with the blues,” Dorsey said, recalling his first exposure to Dranes, “I’ll be able to come up with a gospel style.” Dorsey’s genius was that his songwriting and arrangements were so sophisticated that churchgoers didn’t initially realize his music was based in blues, “the devil’s music”.”

– Extract from ‘He Is My Story: The Sanctified Soul of Arizona Dranes’, by Michael Corcoran, Tompkins Square (2012).

And so the Gospel Blues style was born …

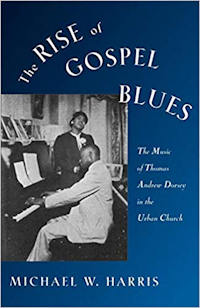

See also Recommended Book ‘The Rise of Gospel Blues’ and associated Critique below.

__________________________________________________________________

Early Gospel Blues Style Artists

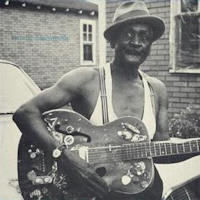

Pearly Brown

Reverend (or Blind) Pearly Brown (August 18, 1915 – June 28, 1986) was an American singer and guitarist, known primarily as a street performer. He also played harmonica and accordion. His repertoire included gospel blues, blues, country, and what he called “slave songs” (i.e. spirituals); but always from a religious standpoint.

Reverend (or Blind) Pearly Brown (August 18, 1915 – June 28, 1986) was an American singer and guitarist, known primarily as a street performer. He also played harmonica and accordion. His repertoire included gospel blues, blues, country, and what he called “slave songs” (i.e. spirituals); but always from a religious standpoint.

Example Song: Keep Your Lamp Trimmed and Burning

Edward W. Clayborn

Reverend Edward W. Clayborn was an American musician, known as the “Guitar Evangelist”. He sang a form of blues gospel similar to Blind Willie Johnson. Clayborn recorded forty songs, for Vocalion Records between 1926 and 1930. In The Ganymede Takeover, the San Franciscan author Philip K. Dick, a record enthusiast, has a character state that “True Religion”, sung by Clayborn was one of the first jazz recordings.

Reverend Edward W. Clayborn was an American musician, known as the “Guitar Evangelist”. He sang a form of blues gospel similar to Blind Willie Johnson. Clayborn recorded forty songs, for Vocalion Records between 1926 and 1930. In The Ganymede Takeover, the San Franciscan author Philip K. Dick, a record enthusiast, has a character state that “True Religion”, sung by Clayborn was one of the first jazz recordings.

Example Song: True Religion

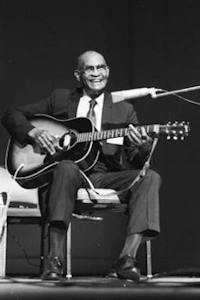

Reverend Gary Davis

Reverend Gary Davis, also Blind Gary Davis (born Gary D. Davis, April 30, 1896 – May 5, 1972), was a blues and gospel singer who was also proficient on the banjo, guitar and harmonica. His fingerpicking guitar style influenced many other artists. His students include Stefan Grossman, David Bromberg, Steve Katz, Roy Book Binder, Larry Johnson, Nick Katzman, Dave Van Ronk, Rory Block, Ernie Hawkins, Larry Campbell, Bob Weir, Woody Mann, and Tom Winslow. He influenced Bob Dylan, the Grateful Dead, Wizz Jones, Jorma Kaukonen, Keb’ Mo’, Ollabelle, Resurrection Band, and John Sebastian (of the Lovin’ Spoonful).

Reverend Gary Davis, also Blind Gary Davis (born Gary D. Davis, April 30, 1896 – May 5, 1972), was a blues and gospel singer who was also proficient on the banjo, guitar and harmonica. His fingerpicking guitar style influenced many other artists. His students include Stefan Grossman, David Bromberg, Steve Katz, Roy Book Binder, Larry Johnson, Nick Katzman, Dave Van Ronk, Rory Block, Ernie Hawkins, Larry Campbell, Bob Weir, Woody Mann, and Tom Winslow. He influenced Bob Dylan, the Grateful Dead, Wizz Jones, Jorma Kaukonen, Keb’ Mo’, Ollabelle, Resurrection Band, and John Sebastian (of the Lovin’ Spoonful).

Example Song: If I Had My Way

Thomas A. Dorsey

Thomas Andrew Dorsey (July 1, 1899 – January 23, 1993) was an American musician. Dorsey was known as “the father of black gospel music” and was at one time so closely associated with the field that songs written in the new style were sometimes known as “dorseys”. Dorsey was the music director at Pilgrim Baptist Church in Chicago, Illinois, from 1932 until the late–1970s.

Thomas Andrew Dorsey (July 1, 1899 – January 23, 1993) was an American musician. Dorsey was known as “the father of black gospel music” and was at one time so closely associated with the field that songs written in the new style were sometimes known as “dorseys”. Dorsey was the music director at Pilgrim Baptist Church in Chicago, Illinois, from 1932 until the late–1970s.

Dorsey’s best-known composition, “Take My Hand, Precious Lord”, was performed by Mahalia Jackson and was a favorite of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. Another composition, “Peace in the Valley”, was a hit for Red Foley in 1951 and has been performed by dozens of other artists, including Albertina Walker (the “Queen of Gospel”), Elvis Presley and Johnny Cash. The Library of Congress added his album Precious Lord: New Recordings of the Great Songs of Thomas A. Dorsey (1973) to the United States National Recording Registry in 2002.

Example Song: Take My Hand, Precious Lord

Blind Roosevelt Graves

Le Moise Roosevelt Graves (December 9, 1909, Meridian, Mississippi – December 30, 1962, Gulfport, Mississippi), credited as Blind Roosevelt Graves, was an American blues guitarist and singer, who recorded both sacred and secular music in the 1920s and 1930s. On all his recordings, he played with his brother Uaroy Graves (c.1912–c.1959), who was also nearly blind and played the tambourine. They were credited as “Blind Roosevelt Graves and Brother”. Their first recordings were made in 1929 for Paramount Records. Theirs is the earliest version recorded of “Guitar Boogie”, and they exemplified the best in gospel singing with “I’ll Be Rested”. Blues researcher Gayle Dean Wardlow has suggested that their 1929 recording “Crazy About My Baby” “could be considered the first rock ‘n’ roll recording.”

Le Moise Roosevelt Graves (December 9, 1909, Meridian, Mississippi – December 30, 1962, Gulfport, Mississippi), credited as Blind Roosevelt Graves, was an American blues guitarist and singer, who recorded both sacred and secular music in the 1920s and 1930s. On all his recordings, he played with his brother Uaroy Graves (c.1912–c.1959), who was also nearly blind and played the tambourine. They were credited as “Blind Roosevelt Graves and Brother”. Their first recordings were made in 1929 for Paramount Records. Theirs is the earliest version recorded of “Guitar Boogie”, and they exemplified the best in gospel singing with “I’ll Be Rested”. Blues researcher Gayle Dean Wardlow has suggested that their 1929 recording “Crazy About My Baby” “could be considered the first rock ‘n’ roll recording.”

Example Song: I’ll Be Rested

Vera Hall

Adell Hall Ward, better known as Vera Hall (April 6, 1902 – January 29, 1964) was an American folk singer, born in Livingston, Alabama. Best known for her 1937 song, “Trouble So Hard”, she was inducted into the Alabama Women’s Hall of Fame in 2005.

Adell Hall Ward, better known as Vera Hall (April 6, 1902 – January 29, 1964) was an American folk singer, born in Livingston, Alabama. Best known for her 1937 song, “Trouble So Hard”, she was inducted into the Alabama Women’s Hall of Fame in 2005.

Example Song: Trouble So Hard

Son House

Eddie James “Son” House, Jr. (March 21, 1902 – October 19, 1988) was an American delta blues singer and guitarist, noted for his highly emotional style of singing and slide guitar playing.

Eddie James “Son” House, Jr. (March 21, 1902 – October 19, 1988) was an American delta blues singer and guitarist, noted for his highly emotional style of singing and slide guitar playing.

After years of hostility to secular music, as a preacher and for a few years also as a church pastor, he turned to blues performance at the age of 25. He quickly developed a unique style by applying the rhythmic drive, vocal power and emotional intensity of his preaching to the newly learned idiom. In a short career interrupted by a spell in Parchman Farm penitentiary, he developed to the point that Charley Patton, the foremost blues artist of the Mississippi Delta region, invited him to share engagements and to accompany him to a 1930 recording session for Paramount Records.

Issued at the start of the Great Depression, the records did not sell and did not lead to national recognition. Locally, House remained popular, and in the 1930s, together with Patton’s associate Willie Brown, he was the leading musician of Coahoma County. There he was a formative influence on Robert Johnson and Muddy Waters. In 1941 and 1942, House and the members of his band were recorded by Alan Lomax and John W. Work for the Library of Congress and Fisk University. The following year, he left the Delta for Rochester, New York, and gave up music. In 2017, his single, “Preachin’ the Blues” was inducted in to the Blues Hall of Fame.

Example Song: Preachin’ the Blues

Bo Weavil Jackson

Bo Weavil Jackson (dates and places of birth and death unknown, real name said to be James Butler) was an African-American blues singer and guitarist. He was one of the first country bluesmen to be recorded, in 1926, for Paramount Records and Vocalion Records. On the latter label he was credited as Sam Butler, which has become the name most commonly used to identify him. His 78-rpm records are highly sought by collectors and have been re-released on numerous LP and CD compilation albums. His technique is distinctive for its upbeat tempo, varied melodic lines, and impromptu instrumentals.

Bo Weavil Jackson (dates and places of birth and death unknown, real name said to be James Butler) was an African-American blues singer and guitarist. He was one of the first country bluesmen to be recorded, in 1926, for Paramount Records and Vocalion Records. On the latter label he was credited as Sam Butler, which has become the name most commonly used to identify him. His 78-rpm records are highly sought by collectors and have been re-released on numerous LP and CD compilation albums. His technique is distinctive for its upbeat tempo, varied melodic lines, and impromptu instrumentals.

It is widely believed that Jackson was active in Birmingham, Alabama since he referred to that area in his lyrics and because that was apparently where the talent scouts found him performing on the street, but he was promoted as originating from North Carolina. According to Eugene Chadbourne, Paramount promoted him as having “come down from the Carolinas”. Apart from his 1926 recordings, no further documentation of him exists.

Example Song: When the Saints Come Marching Home

Blind Lemon Jefferson

Lemon Henry “Blind Lemon” Jefferson (September 24, 1893 – December 19, 1929) was an American blues and gospel singer-songwriter and musician. He was one of the most popular blues singers of the 1920s and has been called the “Father of the Texas Blues”.

Lemon Henry “Blind Lemon” Jefferson (September 24, 1893 – December 19, 1929) was an American blues and gospel singer-songwriter and musician. He was one of the most popular blues singers of the 1920s and has been called the “Father of the Texas Blues”.

Jefferson’s performances were distinctive because of his high-pitched voice and the originality of his guitar playing. His recordings sold well, but he was not a strong influence on younger blues singers of his generation, who could not imitate him as easily as they could other commercially successful artists. Later blues and rock and roll musicians, however, did attempt to imitate both his songs and his musical style.

Example Song: I Want to Be Like Jesus in My Heart

Blind Willie Johnson

Blind Willie Johnson (January 25, 1897 – September 18, 1945) was an American gospel blues singer, guitarist and evangelist. His landmark recordings completed between 1927 and 1930—thirty songs in total—display a combination of powerful “chest voice” singing, slide guitar skills, and originality that has influenced later generations of musicians. Even though Johnson’s records sold well, as a street performer and preacher he had little wealth in his lifetime. His life was poorly documented, but over time music historians such as Samuel Charters have uncovered more about Johnson and his five recording sessions.

Blind Willie Johnson (January 25, 1897 – September 18, 1945) was an American gospel blues singer, guitarist and evangelist. His landmark recordings completed between 1927 and 1930—thirty songs in total—display a combination of powerful “chest voice” singing, slide guitar skills, and originality that has influenced later generations of musicians. Even though Johnson’s records sold well, as a street performer and preacher he had little wealth in his lifetime. His life was poorly documented, but over time music historians such as Samuel Charters have uncovered more about Johnson and his five recording sessions.

A revival of interest in Johnson’s music began in the 1960s, following his inclusion on Harry Smith’s Anthology of American Folk Music, and by the efforts of the blues guitarist Reverend Gary Davis. Johnson’s work has become more accessible through compilation albums such as American Epic: The Best of Blind Willie Johnson and the Charters compilations. As a result, Johnson is credited as one of the most influential practitioners of the blues, and his slide guitar playing, particularly on his hymn “Dark Was the Night, Cold Was the Ground”, is highly acclaimed. Other recordings by Johnson include “Jesus Make Up My Dying Bed”, “It’s Nobody’s Fault but Mine”, and “John the Revelator”.

Example Song: Dark Was the Night, Cold Was the Ground

Booker T. Laury

Lawrence (Booker T.) Laury (September 2, 1914 – September 23, 1995) was an American boogie-woogie, blues, gospel and jazz pianist and singer. Laury worked with Memphis Slim and Mose Vinson but did not record his debut album until he was almost eighty years of age. He appeared in two films – ‘Great Balls of Fire’ and ‘Deep Blues’.

Lawrence (Booker T.) Laury (September 2, 1914 – September 23, 1995) was an American boogie-woogie, blues, gospel and jazz pianist and singer. Laury worked with Memphis Slim and Mose Vinson but did not record his debut album until he was almost eighty years of age. He appeared in two films – ‘Great Balls of Fire’ and ‘Deep Blues’.

Blind Willie McTell

Blind Willie McTell (born William Samuel McTier; May 5, 1898 – August 19, 1959) was a Piedmont blues and ragtime singer and guitarist. He played with a fluid, syncopated fingerstyle guitar technique, common among many exponents of Piedmont blues. Unlike his contemporaries, he came to use twelve-string guitars exclusively. McTell was also an adept slide guitarist, unusual among ragtime bluesmen. His vocal style, a smooth and often laid-back tenor, differed greatly from many of the harsher voices of Delta bluesmen such as Charley Patton. McTell performed in various musical styles, including blues, ragtime, religious music and hokum. McTell left a fine collection of gospel blues songs, including River of Jordan, essentially another version of Nobody’s Fault but Mine. He was related to the bluesman and gospel pioneer Thomas A. Dorsey.

Blind Willie McTell (born William Samuel McTier; May 5, 1898 – August 19, 1959) was a Piedmont blues and ragtime singer and guitarist. He played with a fluid, syncopated fingerstyle guitar technique, common among many exponents of Piedmont blues. Unlike his contemporaries, he came to use twelve-string guitars exclusively. McTell was also an adept slide guitarist, unusual among ragtime bluesmen. His vocal style, a smooth and often laid-back tenor, differed greatly from many of the harsher voices of Delta bluesmen such as Charley Patton. McTell performed in various musical styles, including blues, ragtime, religious music and hokum. McTell left a fine collection of gospel blues songs, including River of Jordan, essentially another version of Nobody’s Fault but Mine. He was related to the bluesman and gospel pioneer Thomas A. Dorsey.

Example Song: Lord Have Mercy, If You Please

Charlie Patton

Charley Patton (died April 28, 1934), also known as Charlie Patton, was an American Delta blues musician. Considered by many to be the “Father of the Delta Blues”, he created an enduring body of American music and inspired most Delta blues musicians. The musicologist Robert Palmer considered him one of the most important American musicians of the twentieth century.

Charley Patton (died April 28, 1934), also known as Charlie Patton, was an American Delta blues musician. Considered by many to be the “Father of the Delta Blues”, he created an enduring body of American music and inspired most Delta blues musicians. The musicologist Robert Palmer considered him one of the most important American musicians of the twentieth century.

Example Song: You’re Gonna Need Somebody When You Die

Washington Phillips

George Washington “Wash” Phillips (January 11, 1880 – September 20, 1954) was an American gospel and gospel blues singer and instrumentalist. The exact nature of the instrument or instruments he played is uncertain, being identified only as “novelty accompaniment” on the labels of the 78rpm records released during his lifetime.

George Washington “Wash” Phillips (January 11, 1880 – September 20, 1954) was an American gospel and gospel blues singer and instrumentalist. The exact nature of the instrument or instruments he played is uncertain, being identified only as “novelty accompaniment” on the labels of the 78rpm records released during his lifetime.

Example Song: I Am Born to Preach the Gospel

D.C. Rice

Reverend D. C. Rice (c. 1888 in Barbour County, Alabama – March 1973 in Montgomery, Alabama) was a preacher and singer. He was raised as a Baptist by his father, and moved to Chicago during World War I. There he joined The Church of the Living God, Pentecostal, and in 1920 became a preacher in this denomination.

Reverend D. C. Rice (c. 1888 in Barbour County, Alabama – March 1973 in Montgomery, Alabama) was a preacher and singer. He was raised as a Baptist by his father, and moved to Chicago during World War I. There he joined The Church of the Living God, Pentecostal, and in 1920 became a preacher in this denomination.

Example Song: The Angels Rolled the Stone Away

Eugene Smith

Eugene Smith (April 22, 1921 – May 9, 2009) was an American gospel singer and composer. In 1933, Smith met Roberta Martin at Ebenezer Missionary Baptist Church when he joined the junior chorus led by Martin. That same year, Smith became one of the original Roberta Martin Singers.

Example Song: Pass Me Not O Gentle Savior

Blind Joe Taggart

Joel Washington Taggart (August 16, 1892 – January 15, 1961), usually known as Blind Joe Taggart, was an African American country blues and gospel singer and guitarist who recorded in the 1920s and 1930s. Though primarily a performer of evangelistic gospel songs, he also recorded secular music under a number of pseudonyms including Blind Joe Amos, Blind Jeremiah Taylor, Blind Tim Russell, Blind Joe Donnel, and possibly Blind Percy and Six Cylinder Smith.

Joel Washington Taggart (August 16, 1892 – January 15, 1961), usually known as Blind Joe Taggart, was an African American country blues and gospel singer and guitarist who recorded in the 1920s and 1930s. Though primarily a performer of evangelistic gospel songs, he also recorded secular music under a number of pseudonyms including Blind Joe Amos, Blind Jeremiah Taylor, Blind Tim Russell, Blind Joe Donnel, and possibly Blind Percy and Six Cylinder Smith.

Example Song: Take Your Burden to the Lord

Sister Rosetta Tharpe

Sister Rosetta Tharpe (March 20, 1915 – October 9, 1973) was an American singer, songwriter, guitarist, and recording artist. She attained popularity in the 1930s and 1940s with her gospel recordings, characterized by a unique mixture of spiritual lyrics and rhythmic accompaniment that was a precursor of rock and roll. She was the first great recording star of gospel music and among the first gospel musicians to appeal to rhythm-and-blues and rock-and-roll audiences, later being referred to as “the original soul sister” and “the Godmother of rock and roll”. She influenced early rock-and-roll musicians, including Little Richard, Johnny Cash, Carl Perkins, Chuck Berry, Elvis Presley and Jerry Lee Lewis.

Sister Rosetta Tharpe (March 20, 1915 – October 9, 1973) was an American singer, songwriter, guitarist, and recording artist. She attained popularity in the 1930s and 1940s with her gospel recordings, characterized by a unique mixture of spiritual lyrics and rhythmic accompaniment that was a precursor of rock and roll. She was the first great recording star of gospel music and among the first gospel musicians to appeal to rhythm-and-blues and rock-and-roll audiences, later being referred to as “the original soul sister” and “the Godmother of rock and roll”. She influenced early rock-and-roll musicians, including Little Richard, Johnny Cash, Carl Perkins, Chuck Berry, Elvis Presley and Jerry Lee Lewis.

Tharpe was a pioneer in her guitar technique; she was among the first popular recording artists to use heavy distortion on her electric guitar, presaging the rise of electric blues. Her guitar playing technique had a profound influence on the development of British blues in the 1960s; in particular a European tour with Muddy Waters in 1963 with a stop in Manchester is cited by prominent British guitarists such as Eric Clapton, Jeff Beck, and Keith Richards.

Willing to cross the line between sacred and secular by performing her music of “light” in the “darkness” of nightclubs and concert halls with big bands behind her, Tharpe pushed spiritual music into the mainstream and helped pioneer the rise of pop-gospel, beginning in 1938 with the recording “Rock Me” and with her 1939 hit “This Train”. Her unique music left a lasting mark on more conventional gospel artists such as Ira Tucker, Sr., of the Dixie Hummingbirds. While she offended some conservative churchgoers with her forays into the pop world, she never left gospel music.

Tharpe’s 1944 release “Down by the Riverside” was selected for the National Recording Registry of the U.S. Library of Congress in 2004, which noted that it “captures her spirited guitar playing and unique vocal style, demonstrating clearly her influence on early rhythm-and-blues performers” and cited her influence on “many gospel, jazz, and rock artists”. (“Down by the Riverside” was recorded by Tharpe on December 2, 1948, in New York City, and issued as Decca single 48106.) Her 1945 hit “Strange Things Happening Every Day”, recorded in late 1944, featured Tharpe’s vocals and electric guitar, with Sammy Price (piano), bass and drums. It was the first gospel record to cross over, hitting no. 2 on the Billboard “race records” chart, the term then used for what later became the R&B chart, in April 1945. The recording has been cited as a precursor of rock and roll. On December 13, 2017, Tharpe was chosen for induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame as an Early Influence.

Example Song: This Train (is Bound For Glory)

Bukka White

Booker T. Washington “Bukka” White (November 12, 1906 – February 26, 1977) was an African-American Delta blues guitarist and singer. Bukka is a phonetic spelling of White’s first name; he was named after the African-American educator and civil rights activist Booker T. Washington.

Booker T. Washington “Bukka” White (November 12, 1906 – February 26, 1977) was an African-American Delta blues guitarist and singer. Bukka is a phonetic spelling of White’s first name; he was named after the African-American educator and civil rights activist Booker T. Washington.

Example Song: The Promise True and Grand

Josh White

Joshua Daniel White (February 11, 1914 – September 5, 1969) was an American singer, guitarist, songwriter, actor and civil rights activist. He also recorded under the names Pinewood Tom and Tippy Barton in the 1930s.

Joshua Daniel White (February 11, 1914 – September 5, 1969) was an American singer, guitarist, songwriter, actor and civil rights activist. He also recorded under the names Pinewood Tom and Tippy Barton in the 1930s.

White grew up in the South during the 1920s and 1930s. He became a prominent race records artist, with a prolific output of recordings in genres including Piedmont blues, country blues, gospel music, and social protest songs. In 1931, White moved to New York, and within a decade his fame had spread widely. His repertoire expanded to include urban blues, jazz, traditional folk songs, and political protest songs, and he was in demand as an actor on radio, Broadway, and film. He recorded religious songs for ARC, billed as “Joshua White, the Singing Christian”.

Example Song: Jesus Gonna Make Up My Dyin’ Bed

Elder Roma Wilson

Elder Roma Wilson (December 22, 1910 – October 25, 2018) was an American gospel harmonica player and singer. A clergyman, Wilson discovered he had a degree of notability later in his life, having previously been unaware of interest in his work.

Elder Roma Wilson (December 22, 1910 – October 25, 2018) was an American gospel harmonica player and singer. A clergyman, Wilson discovered he had a degree of notability later in his life, having previously been unaware of interest in his work.

Example Song: This Train Is a Clean Train

Robert Wilkins

Robert Timothy Wilkins (January 16, 1896 – May 26, 1987) was an American country blues guitarist and vocalist, of African-American and Cherokee descent. His distinction was his versatility: he could play ragtime, blues, minstrel songs, and gospel music with equal facility.

Robert Timothy Wilkins (January 16, 1896 – May 26, 1987) was an American country blues guitarist and vocalist, of African-American and Cherokee descent. His distinction was his versatility: he could play ragtime, blues, minstrel songs, and gospel music with equal facility.

Example Song: The Prodigal Son

Sources: Wikipedia extracts et al

__________________________________________________________________

Recommended Book

‘The Rise of Gospel Blues: The music of Thomas Andrew Dorsey in the Urban Church’

‘The Rise of Gospel Blues: The music of Thomas Andrew Dorsey in the Urban Church’

by Michael W. Harris

Published by Oxford University Press (1992)

ISBN: 0-19-509057-8

Critique by Tony Thomas:

This book belongs on every bookshelf of anyone who is seriously concerned with African American folk and popular music, secular and religious. Harris does a good job describing not only the details of Dorsey’s life, but setting him in the musical worlds he inhabited in the early 20th Century. My current research work does not include religious music, and I have been doing a lot of work on ragtime and the origins of the Blues as they related to the five string banjo. This book provided new insights on the nature of the Blues, on the relationship between the vaudeville Blues, Downhome Blues, and jazz in the 1920s that recent reading on Jelly Roll Morton, and the origins of Jazz and the Blues did not. At the same time, the book provides broad and objective coverage of major trends in the Black church especially the National Baptist Convention in the first thirty years of the 20th Century.

Besides that he speaks of Dorsey and the origin of Blues Gospel. Put shortly, Black religious music in the early 20th century was dominated by forces who wanted to squelch African originated forms of religion and worship and impose European and European American models for services and music. In the Chicago of the 1920s, the major churches were dominated by music and choir directors who had been trained in Europe to produce superb classical religious music and any kind of African American singing and praise and testifying was often banned from the church as a whole or from the Sunday service.

The pressure of Black migration from the South placed a demand on conservative churches to hold onto their congregations. After a career as a mediocre Blues pianist, more successful arranger and band leader for Ma Rainey, while enjoying success in the Blues as George Tom, well known for his dirty songs, Dorsey crafted gospel songs and more importantly gospel performance patterns modeled after the music and the acts put on by successful Blues singers. He first worked with a former preacher singing his songs and walking in rhythm around churches. When they were first able to perform this way, Dorsey – always the accompanist – would stand up at the piano, while this preacher danced and strutted as he sang his song. The congregation got wild.

Dorsey’s goal seemed to be advancing his music publishing business by popularizing his songs with soloists. It was almost an after-thought that in accepting a lucrative position as music director at a major Chicago Baptist church that he set up a gospel chorus, a move that was copied and duplicated as the blues-gospel movement swept the country.

The blues gospel approach provided a compromise. The old line preachers were fundamentally against African forms of congregational worship, singing by the whole church, the old church rock songs, testifying and other African aspects of religion. Gospel offered the music in a contained form, not done by the whole congregation, but performed by a contained gospel soloist or gospel choir, and presenting a limited period in which shouting, testifying, and praising in the old way was possible without transforming the service.

Throughout, Dorsey was not shy in judging his success as a commercial venture. He speaks about success in the number of employees and the amount of space he had shipping out sheet music. Since his aims were to give religious music the music feel and performance style of blues entertainment, it is hardly surprising that Blues Gospel especially in the person of Dorsey’s great protégé Mahalia Jackson became first an informal form of entertainment within the Black church world, and then a form that could be found in night clubs, variety shows, and jazz concert.

A lot of thought should be given to the importance of the gospel blues. Post WWII Black popular music began with waning swing singers and older Blues singers leading off R & B. However, the generations of Black R & B singers since the late 1940s have almost exclusively come out of the gospel music industry on the top or the bottom. Soul music beginning with Ray Charles’ break into his own voice in the 1950s is not much more than adding the techniques and approaches of the gospel of the 1950s and 1960s to secular music. In this sense it returns to secular music what the religious music had received from Dorsey’s Blues.

However, if Dorsey had not figured out how to legitimate Blues music style with the established Black church, the opening to perform this kind of Black music by the religious authorities was important to keeping the music going. One should remember the degree to which Black churches outside the holiness churches, particularly in the South, forbade or condemned secular music and Blues. Now, I believe whether Dorsey or some other individual had done it, African religious and music traditions would have fought their way back into Black churches. Yet, if there hadn’t been a Thomas Dorsey, it might have been harder, and more distance might have been made between Black religious and secular music.

__________________________________________________________________

Recommended CD Compilations

There are many Gospel Blues albums available by individual artists, here are two compilation albums:

The Rough Guide to Gospel Blues

The Rough Guide to Gospel Blues

Various Artists

Label: World Music Network

Various Artists

Label: X5 Music Group

__________________________________________________________________

Further References

Coming soon

__________________________________________________________________